Plastic is everywhere because it’s tough and waterproof. However, those same traits are what make plastic harmful to the environment. It really is a double-edged sword.

For years, scientists have tried to swap plastic for biomaterials, but most “green” materials get weak the moment they get wet.

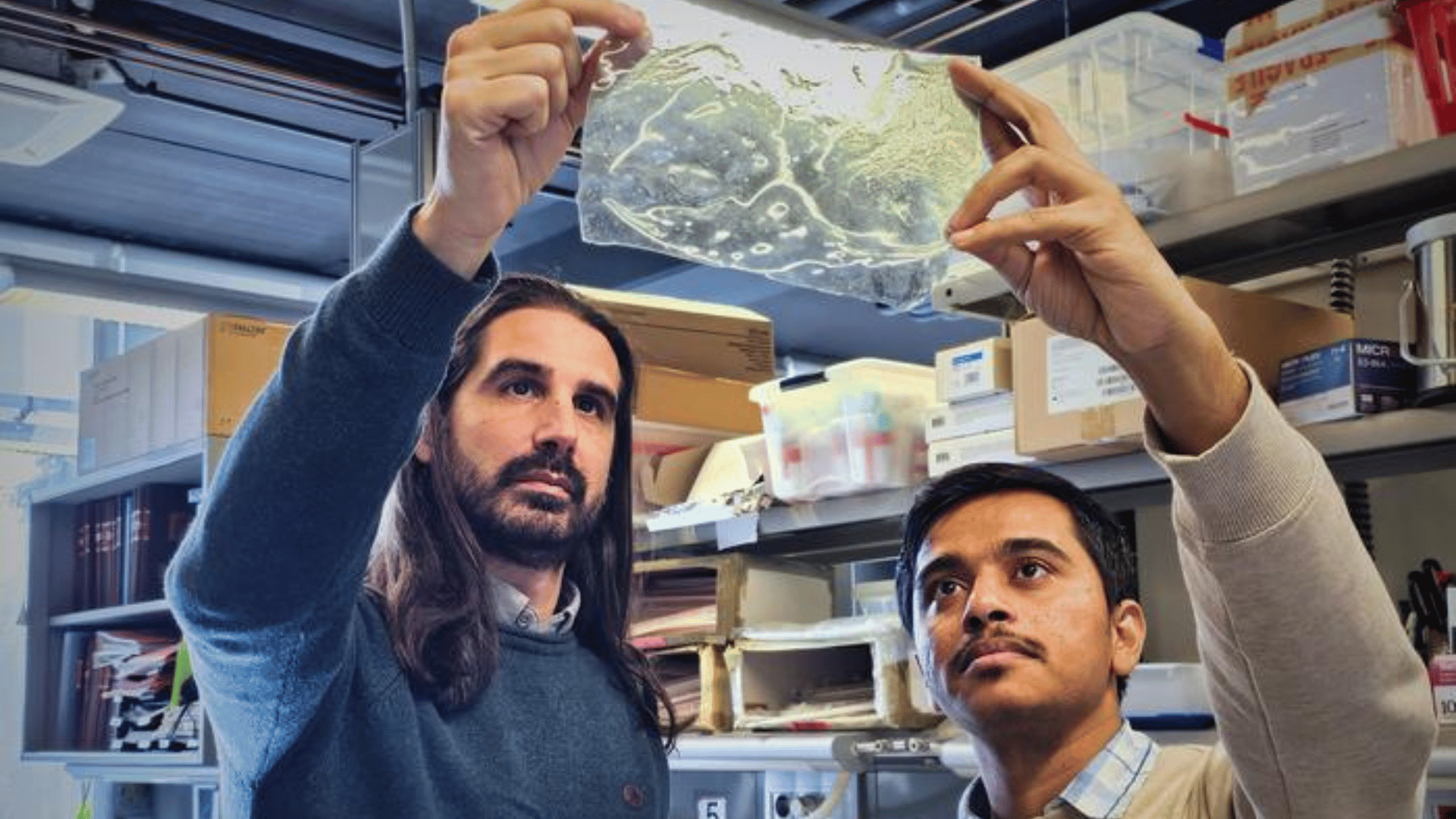

Researchers at the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia (IBEC) and the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) found a solution to biomaterials breaking down if they get wet. Instead of fighting water, they’ve created a material that actually gets stronger when it’s soaked.

Learning from Nature

The team looked at how insects, specifically sandworms, build their shells. They focused on chitosan, a substance found in shrimp shells and mushrooms. By adding a tiny bit of nickel to the mix, they created a material that uses water instead of resisting it. When the material hits the water, the molecules reconfigure themselves, making the structure up to 50% stronger.

“The material is still biologically pure in the eyes of nature; it remains essentially the same molecule found in insect shells or mushrooms,” said Javier G. Fernández, the lead researcher on the study.

Most of the time, we try to make materials “inert” so the environment can’t touch them. “This research shows the opposite,” Fernández said. “Materials can thrive by interacting with their environment rather than isolating themselves from it.”

Zero Waste

Additionally, the production process is green and clean. The team figured out how to reuse 100% of the nickel involved, creating a closed loop where nothing is wasted.

It’s also easy to scale up because chitosan is the second most common organic molecule on the planet. “Each year, the world produces an estimated one hundred billion tons of chitin, equivalent to three centuries’ worth of plastic production,” said Akshayakumar Kompa, the study’s first author.

Moreover, you don’t need a massive global supply chain. You can get chitosan from local food waste or fungal by-products. The goal is to make things where the materials already are.

While we might see this first in fishing gear or farm packaging, researchers believe there is a lot of potential. “This is the first study,” Fernández said. “Now that we know this effect exists, we and others can search for new materials and new ways to achieve it.”