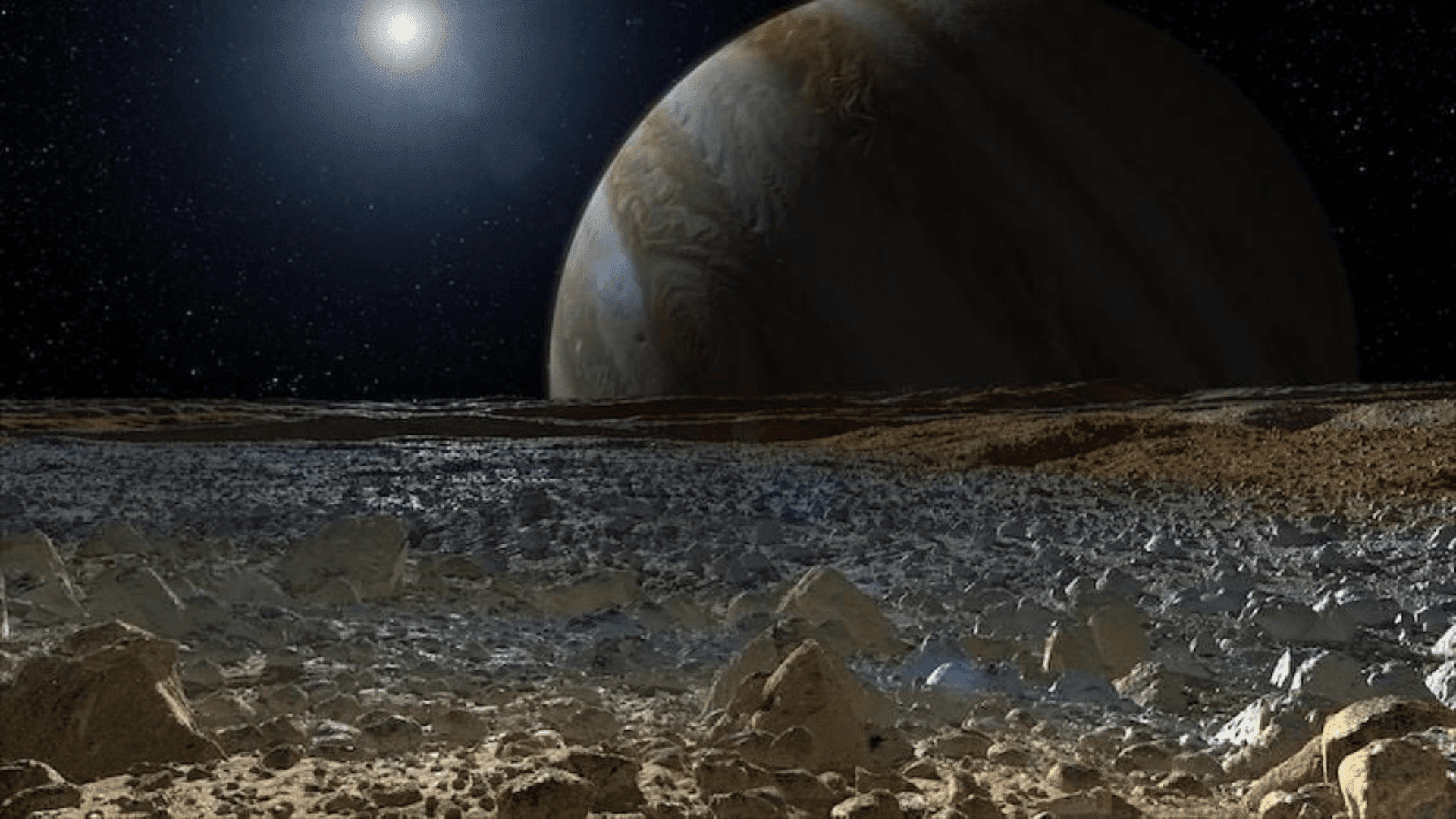

New observations by the James Webb Space Telescope have identified carbon dioxide originating from one of Jupiter’s moons, Europa.

Carbon may exist beneath the surface of the moon’s icy surface according to two new studies. Given that carbon is an essential element for life on Earth, this strengthens the moon’s potential for hosting extraterrestrial life.

Europa has long been considered as a possible area for the existence of extraterrestrial life. This is because the 2,000-mile-wide moon is covered with a 10 to 15-mile-thick coating of ice.

It may initially seem like an unlikely space for life to form given that the surface temperatures on Europa range from minus 210 to minus 370 degrees Fahrenheit. The moon orbits Jupiter in an oval or egg shape, so it’s constantly being moved in and out of the planet’s gravitational pull.

Researchers have speculated that this pattern could be kneading the moon, causing heat to form beneath the icy surface and creating a salty ocean that stretches approximately 40 to 100 miles deep. This would mean that the moon contains more water than twice the volume of the Earth’s oceans combined.

“For life, you need liquid water, the right chemistry, a source of energy, and enough time for life to develop,” Andrew Coates, a physicist at University College London’s Mullard Space Science Laboratory who was not involved in the work, tells the Guardian. “We think all of those may be present on Europa.”

Though scientists had previously detected carbon dioxide on Europa’s surface, they could not determine whether the carbon originated from an external source (such as a meteorite) or from the ocean that lies beneath the moon’s icy surface. A new analysis by the James Webb Space Telescope, however, indicates that the carbon originated from Europa.

“This is a big deal, and I am very excited by it,” stated Christopher Glein, a geochemist at Southwest Research Institute and co-author of a new paper about the discovery. “We don’t know yet if life is actually present in Europa’s ocean. But this new finding adds evidence to the case that Europa’s ocean would be a good bet for hosting extant life. That environment looks tantalizing from the perspective of astrobiology.”

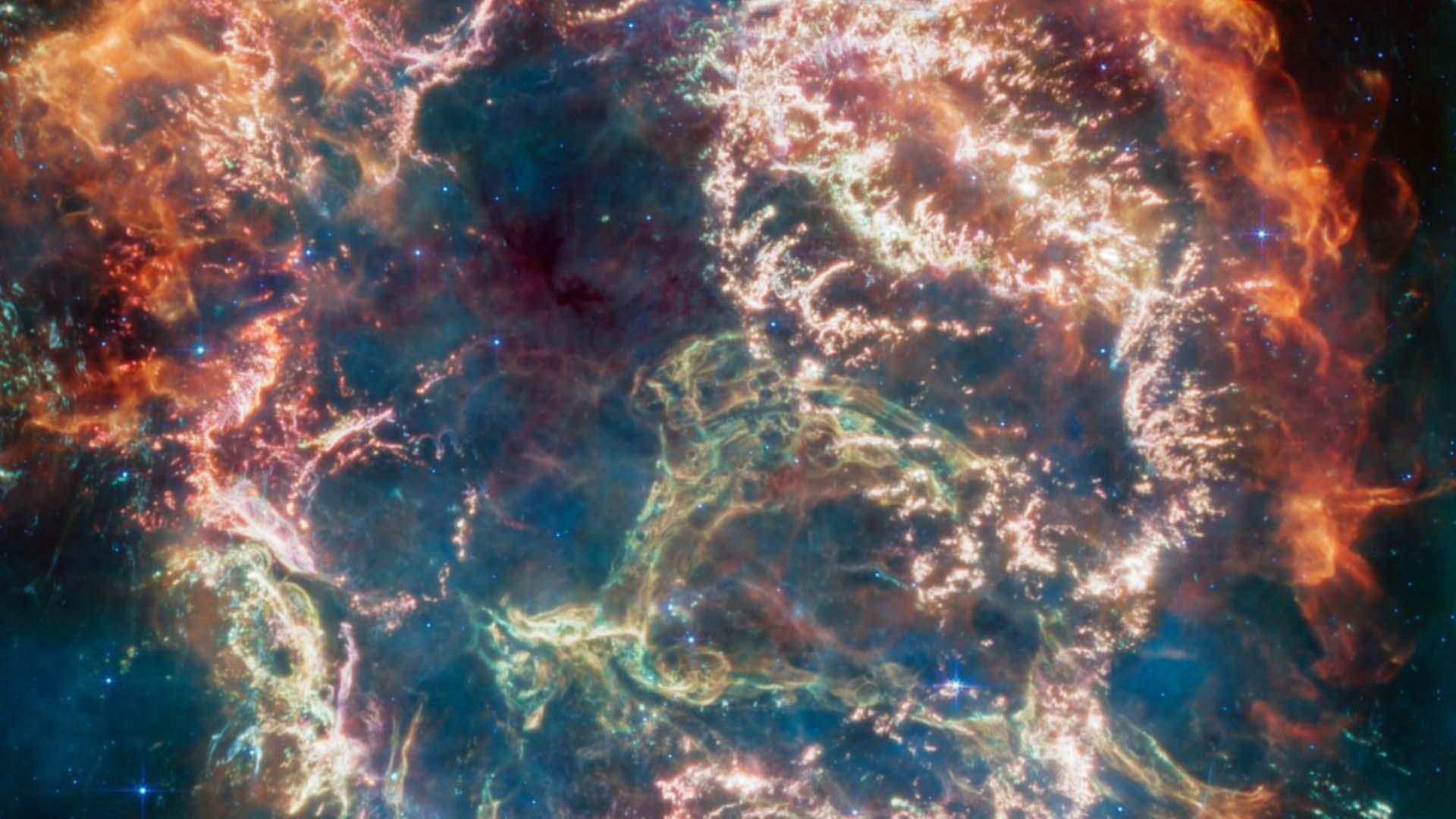

The telescope’s observations were analyzed by two independent teams, both publishing papers reporting their conclusions in Science. The researchers found that carbon dioxide was most abundant in Tara Regio, an area of the moon with a geologically young surface called “chaos terrain.”

“It’s exactly what it sounds like. It’s chaotic,” said Emily Martin, a planetary geologist at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum who was not involved in either new study. “What we think is happening, when it comes to chaos terrain, is that at some point, the surface got warm enough to break up into these little ice rafts—in some cases, large ice rafts—so that the entirety of Tara Regio is these broken-up puzzle pieces floating around in this now-solidified, icy, slushy matrix.”

On the icy crust of Jupiter's moon Europa, Webb has discovered carbon dioxide that likely originated in the liquid water ocean below. Understanding the chemistry of this ocean could help determine if it is a good place for life as we know it: https://t.co/tGLrJrVsyl pic.twitter.com/4C4JjZMCBw

— NASA Webb Telescope (@NASAWebb) September 21, 2023

The moon’s surface has been disrupted in this region, possibly leading to an exchange of material between the ice and ocean beneath which could allow carbon dioxide from the water to come to the surface.

NASA plans to launch its Europa Clipper spacecraft in 2024, the first mission that will conduct a detailed reconnaissance of the icy moon. Researchers hope that this will allow them to gain further insights regarding the moon’s potential for extraterrestrial life.