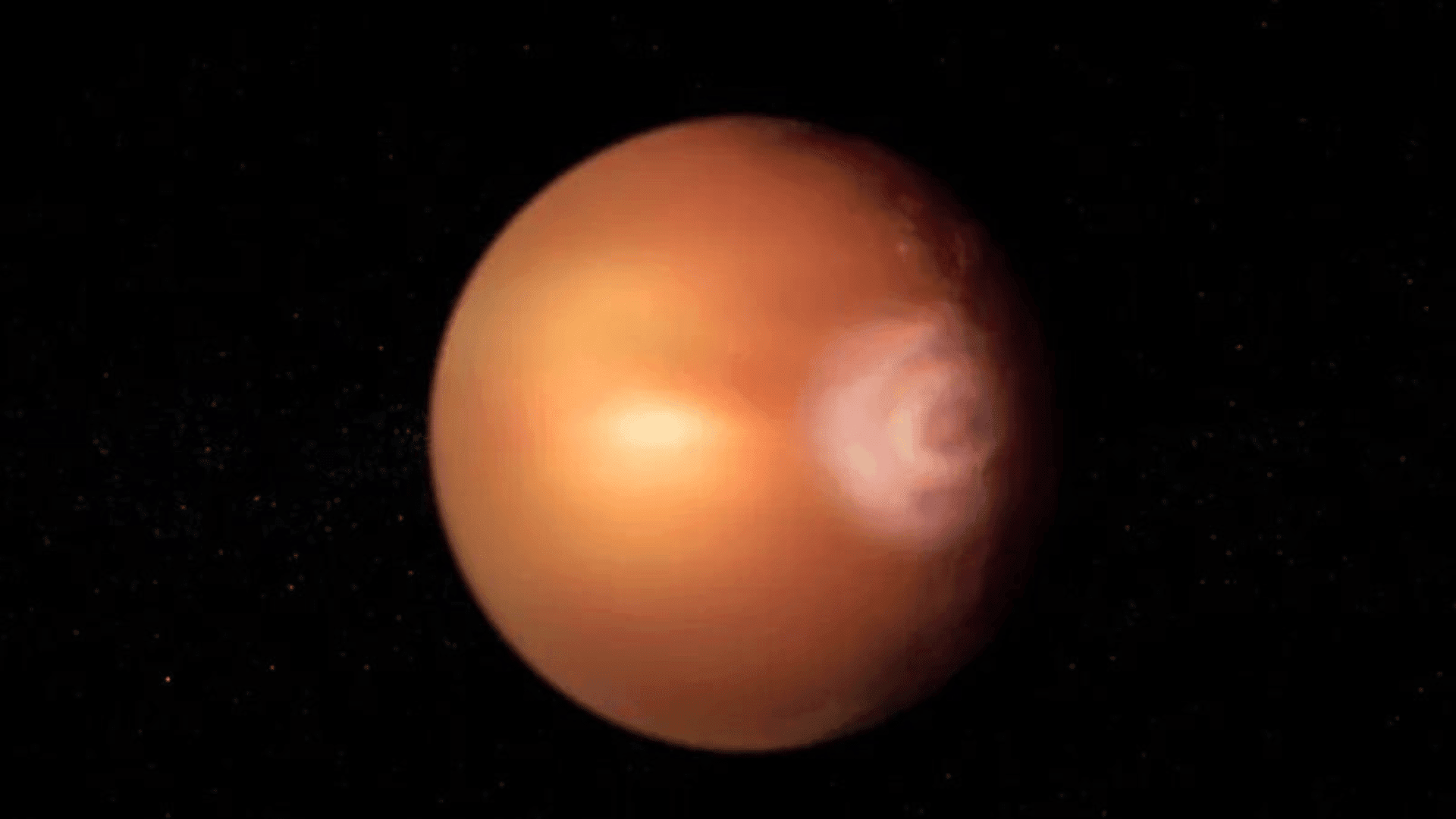

Astronomers have found evidence of a meteorological phenomenon that resembles a rainbow, also known as the glory effect, on another planet outside of the solar system. The planet is called WASP-76b and it’s located approximately 637 light-years away.

A glory includes one or more circular rings that consist of the colors of the rainbow, with red on the outside and violet on the inside. Their name originates from their appearance as they look like halos around the heads of saints in medieval paintings.

Also caused by the bending of light by water droplets, glories are different than rainbows because backscattered light is diffracted between the water droplets, rather than refracted when entering and leaving them. Even on Earth they are very rare and can only be spotted when looking down at one’s shadow from a significant height.

Apart from Earth, the phenomenon has only ever been recorded on Venus. The European Space Agency (ESA) spotted the glory effect in the clouds of Venus in 2014.

“There’s a reason no glory has been seen before outside our solar system – it requires very peculiar conditions,” Olivier Demangeon, from the Institute of Astrophysics and Space Sciences in Portugal, said to BBC.

WASP-76b is very close to its star so its environment is so hot that it’s thought to rain iron. Thought to also be tidally locked, the exoplanet has a permanent daylight side where temperatures reach approximately 4,350°F. Though the night side is cooler, it has violent winds caused by the temperature differences.

Explore Tomorrow's World from your inbox

Get the latest science, technology, and sustainability content delivered to your inbox.

I understand that by providing my email address, I agree to receive emails from Tomorrow's World Today. I understand that I may opt out of receiving such communications at any time.

At the borderline between the two sides, metals vaporized on the day side condense and fall as rain. The ESA’s Characterizing Exoplanet Satellite (Cheops) spotted an unexpected pattern of light, noting an asymmetry in WASP-76b’s edges as it moves across its star with the entry to the transit brighter than the exit.

Dr Olivier Demangeon of Portugal’s Institute of Astrophysics and Space Sciences and colleagues sought help from other space telescopes to determine what they had witnessed. Neither Hubble or Spitzer could figure it out, but Cheops monitored WASP-76b for 23 transits over three years, data from TESS provided the match they needed.

“This discovery leads us to hypothesize that this unexpected glow could be caused by a strong, localized, and anisotropic (directionally dependent) reflection – the glory effect,” Demangeon said in a statement to IFLScience.

Though on Earth water droplets cause glories, that doesn’t necessarily mean there’s proof of water on WASP-76b. Approximately 20 types of ions, atoms, and molecules have been identified on the exoplanet’s atmosphere and one of these, or something else that is spherical and highly reflective not yet uncovered, could produce the glory effect.

Though further research is required to prove the phenomenon with certainty, it may help astronomers gain a better understanding of exoplanets and their potential habitability. Scientists plan to use NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to study WASP-67b and potentially confirm the glory effect.