Scientists are taking a page out of nature’s playbook to change how robots move. If you look at a human knee, it doesn’t just swing back and forth like a simple door hinge. It actually rolls, glides, and shifts to keep us balanced.

Researchers at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) have figured out a way to bring that same fluid motion to machines. They’ve developed a new method to design “rolling contact joints,” curved surfaces that roll against each other, to make robots move more like animals and less like clunky pieces of hardware.

From Software to Hardware

Usually, when a robot needs to move a certain way, engineers rely on complex software to tell the motors exactly what to do. The Harvard team wants to change that. By using a new mathematical approach, they can design the physical shape of the joint to handle the hard work.

“We try to think about robot design as being closely coupled with task and control,” said Robert J. Wood, the Harry Lewis and Marlyn McGrath Professor of Engineering and Applied Sciences. “We aim to offload as much motion control as possible to the mechanics and materials of the robot, so that the control system can focus on task-level goals. Colter’s methods do exactly that, and in a very elegant way, both mathematically and mechanically.”

By letting the joint’s physical shape dictate the movement, robots can use smaller motors because the energy is sent exactly where it’s needed. Ph.D. student Colter Decker said, “If we can embed those decisions into the mechanics of the robot itself, then we can create robots that are more efficient.”

Better Braces and Stronger Grips

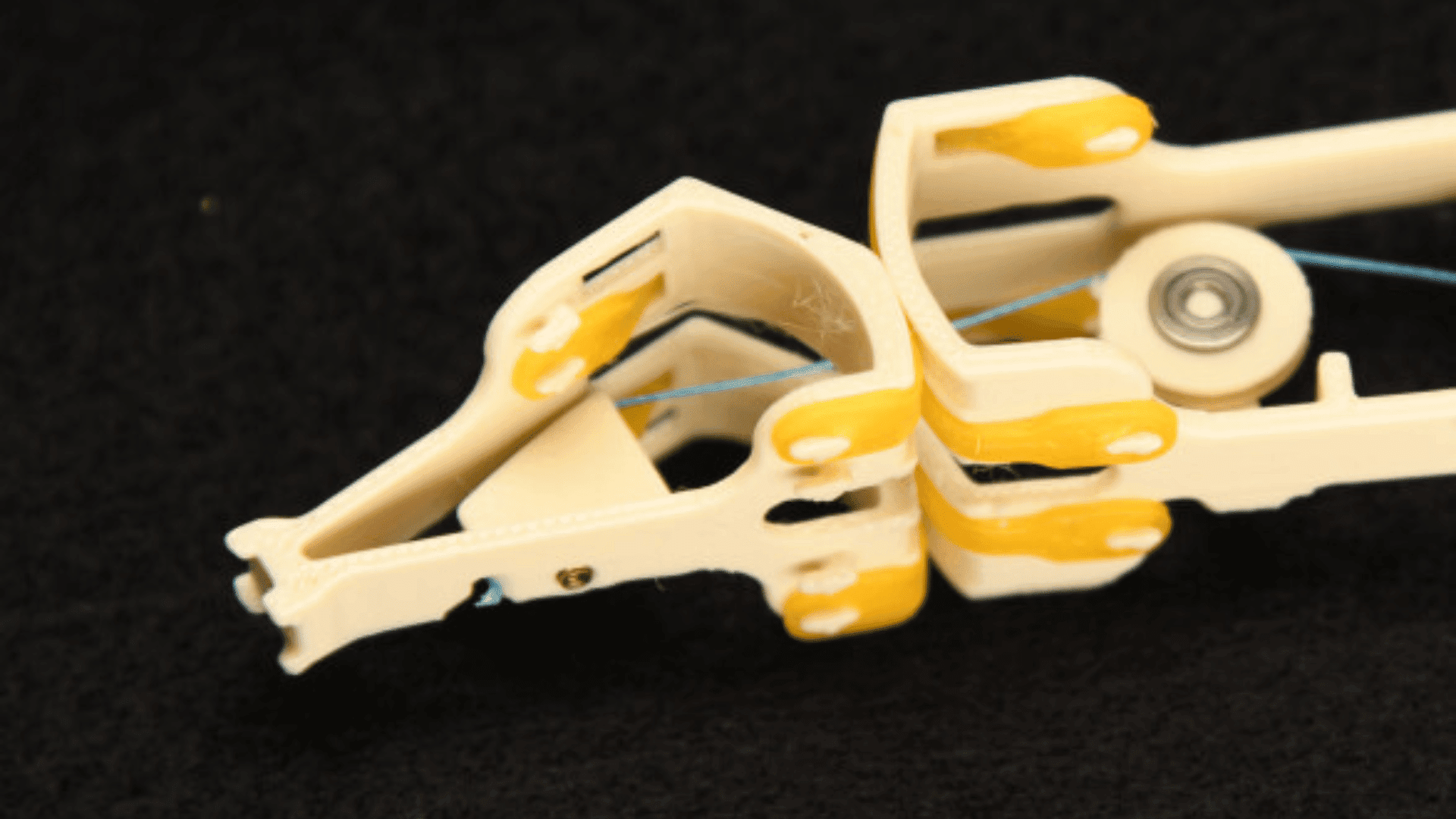

To see if this actually worked, the team built two different prototypes: a robotic gripper and a knee-like joint.

When they applied this design to a knee joint, it followed the natural path of a human leg so closely that it fixed alignment issues by 99% compared to standard designs. This is a significant result for people who use knee braces or exoskeletons, which can often be uncomfortable because they don’t move the way a real body does.

According to researchers, the robotic gripper was just as successful. By shaping the joints specifically for the task of grabbing, the gripper could hold three times more weight than a standard version.

“We did a bunch of math to say, if you have some specific desired trajectory that you want the joint to follow, and you have some specific force transmission ratio along that trajectory, can we find surfaces and pulleys that will exhibit those properties?” Decker said. “Then we can apply that design process to optimize joints for tasks like walking, jumping, or grabbing.”