Scientists at Northwestern University have found a new, and potentially better way to build vaccines, and it doesn’t involve adding new ingredients. Instead, they discovered that simply rearranging how a vaccine is put together can make it much more effective at fighting cancer.

Traditionally, to make a vaccine, researchers would take the parts that trigger an immune response and the parts that target the disease, mix them together, and inject the cocktail. However, the Northwestern team found that the immune system is very particular about how those parts are organized.

A New Way to Fight Cancer

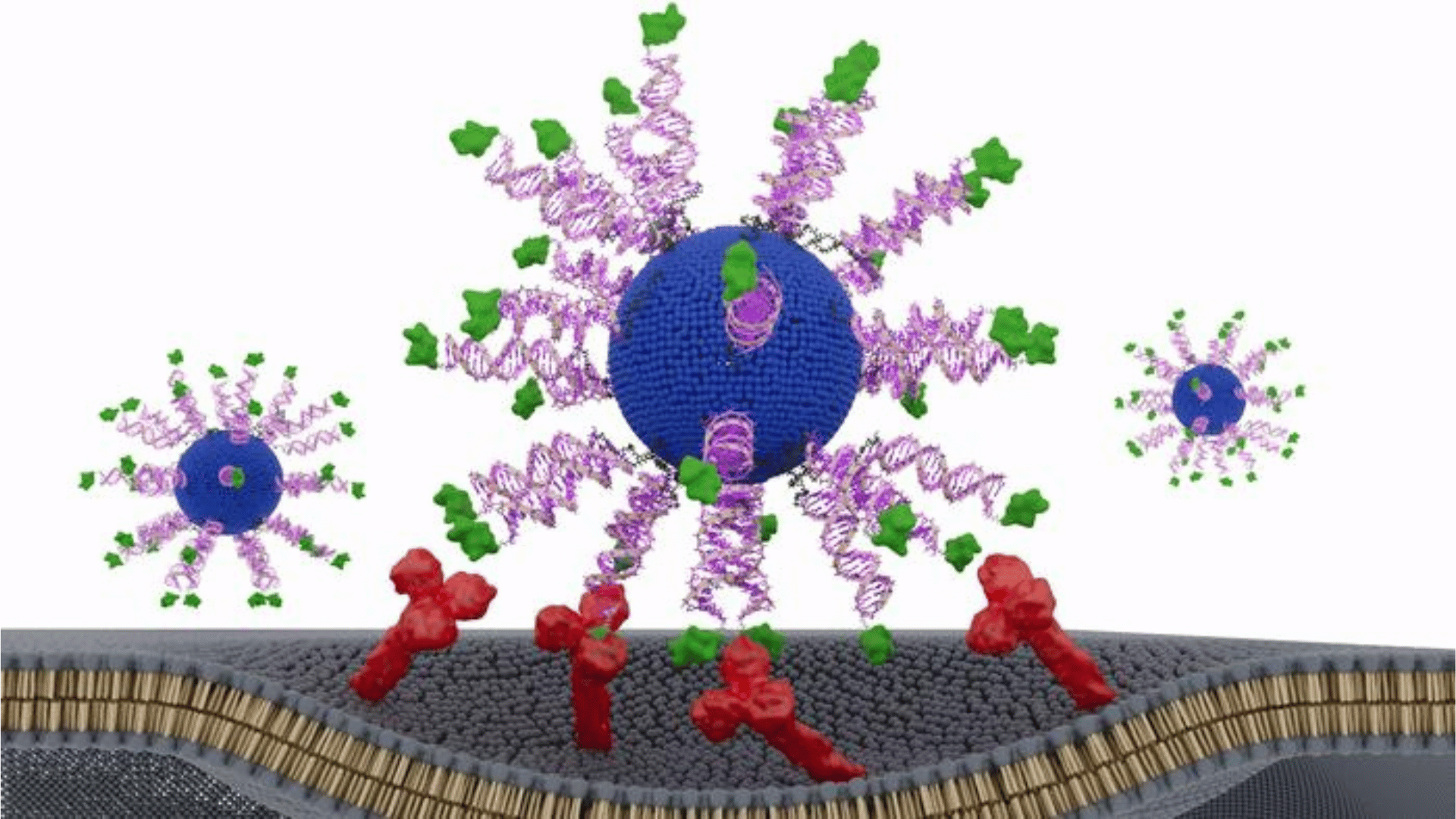

The team focused on HPV-driven cancers, which include cervical and various head and neck cancers. While we already have vaccines to prevent HPV, they don’t help people who already have the disease. To fix this, the researchers built “spherical nucleic acids” (SNAs). These are tiny, ball-shaped structures made of DNA that are great at getting inside immune cells.

They tested several versions of these vaccines. Every version had the exact same ingredients, but the team placed the cancer-targeting pieces in different spots, some inside the ball and some on the outside. They even flipped the pieces to see if the direction they faced mattered.

It turns out, one specific arrangement outperformed all the others, shrinking tumors and helping the body create more “killer” T cells to attack the cancer.

“There are thousands of variables in the large, complex medicines that define vaccines,” said Chad A. Mirkin, who led the study. “The promise of structural nanomedicine is being able to identify from the myriad possibilities the configurations that lead to the greatest efficacy and least toxicity. In other words, we can build better medicines from the bottom up.”

Geometry Matters

The researchers found that when the vaccine was put together correctly, the immune system processed it much better. In tests with patient samples, the best-designed vaccine killed two to three times more cancer cells than the others.

“This effect did not come from adding new ingredients or increasing the dose,” said Dr. Jochen Lorch, who co-led the study. “It came from presenting the same components in a smarter way. The immune system is sensitive to the geometry of molecules. By optimizing how we attach the antigen to the SNA, the immune cells processed it more efficiently.”

This discovery could mean that some vaccines that failed in the past weren’t actually “bad.” They might have just been put together the wrong way. By changing the structure, scientists might be able to turn those failed attempts into powerful treatments.

“We may have passed up perfectly acceptable vaccine components because simply because they were in the wrong configurations,” Mirkin said. “We can go back to those and restructure and transform them into potent medicines.”

“The whole concept of structural nanomedicines is a major train roaring down the tracks. We have shown that structure matters — consistently and without exception,” Mirkin concluded.