Many professions rely on having a voice. Whether it’s a professional singer, a teacher, or a public speaker, losing one’s voice can be detrimental to their career. It impacts a person’s mental health, quality of life, and, in some cases, one’s livelihood.

When scarring forms on the delicate vocal cords following an injury, it often results in permanent voice loss.

However, a recent study from McGill University found a potential long-term solution. Researchers developed a novel injectable hydrogel that is engineered to outlast existing treatments.

Current therapeutic injections are often temporary, which is a significant issue. Materials often break down too quickly and patients are forced to undergo repeated procedures. As a result, the fragile vocal cord tissue could suffer further damage. A team of McGill scientists recognized this and developed the new gel that resists breakdown for weeks.

Longer-Lasting Treatment for Voice Loss

Advertisement

Their study was published in the journal Biomaterials. The researchers reported that the gel utilizes an advanced technique that makes it last longer. The gel is made from natural tissue proteins. Researchers used a process called click chemistry to structurally enhance the material. This innovation is what gives the treatment its edge.

“This process is what makes our approach unique,” said co-senior author Maryam Tabrizian. “It acts like a molecular glue, locking the material together so it doesn’t fall apart too quickly once injected.”

The extended stability was validated in both lab and animal tests. According to the scientists, it gives the vocal cords a much-needed window of time to heal without repeated intervention.

There is a critical need for such a solution. According to the U.S. National Institutes of Health, roughly one in 13 adults experiences a voice disorder each year. Injuries are especially prevalent among older adults who suffer from acid reflux, those who smoke, and individuals who use their voices professionally.

Senior author Nicole Li-Jessen, a clinician-scientist in McGill’s School of Communication Sciences and Disorders, said, “People take their voices for granted, but losing it can deeply affect mental health and quality of life, especially for those whose livelihoods depend on it.”

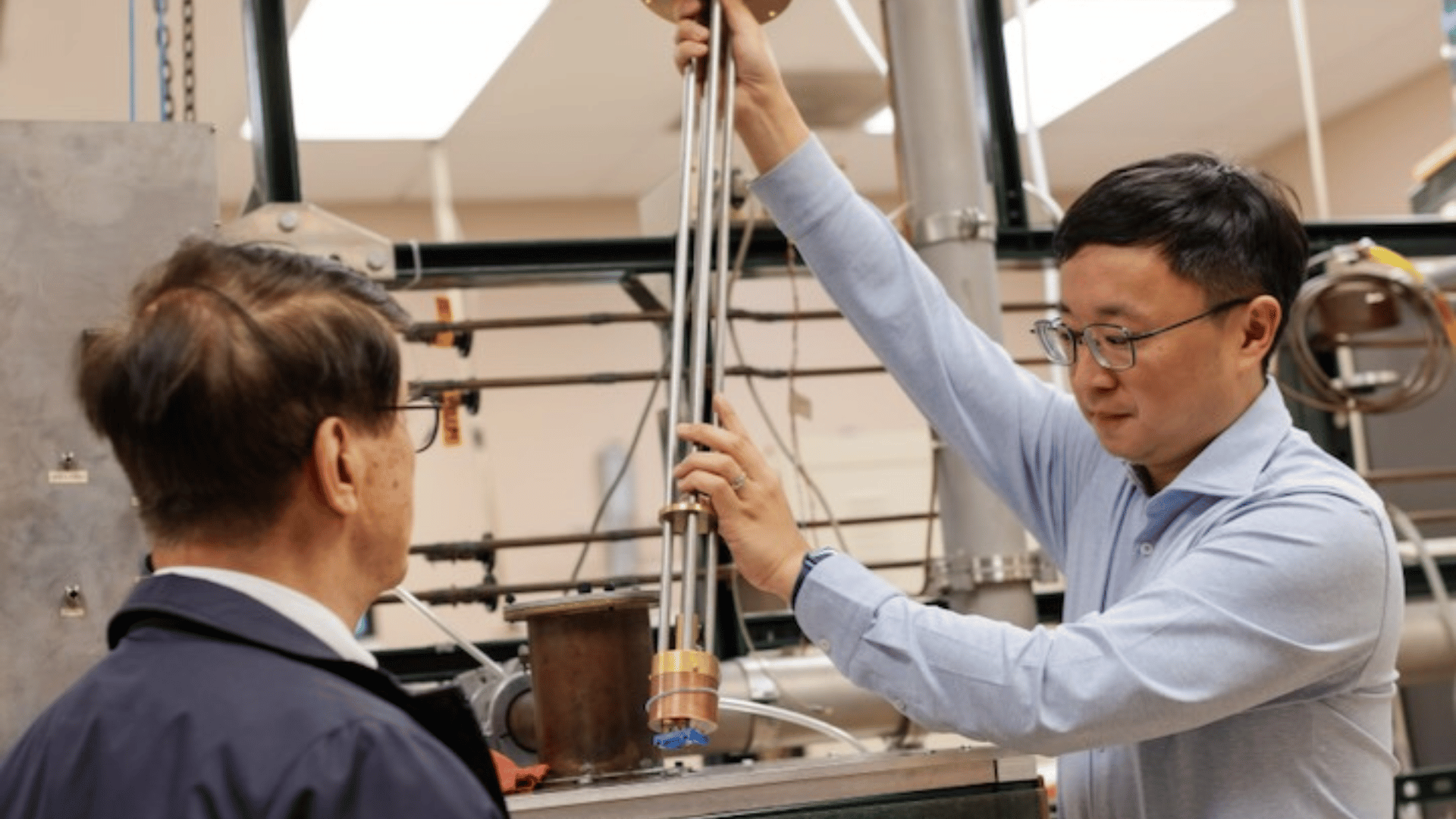

The researchers are now focusing on computer simulations to precisely mimic the gel’s behavior in the human body. If these results are validated, the team hopes to move swiftly toward human trials.