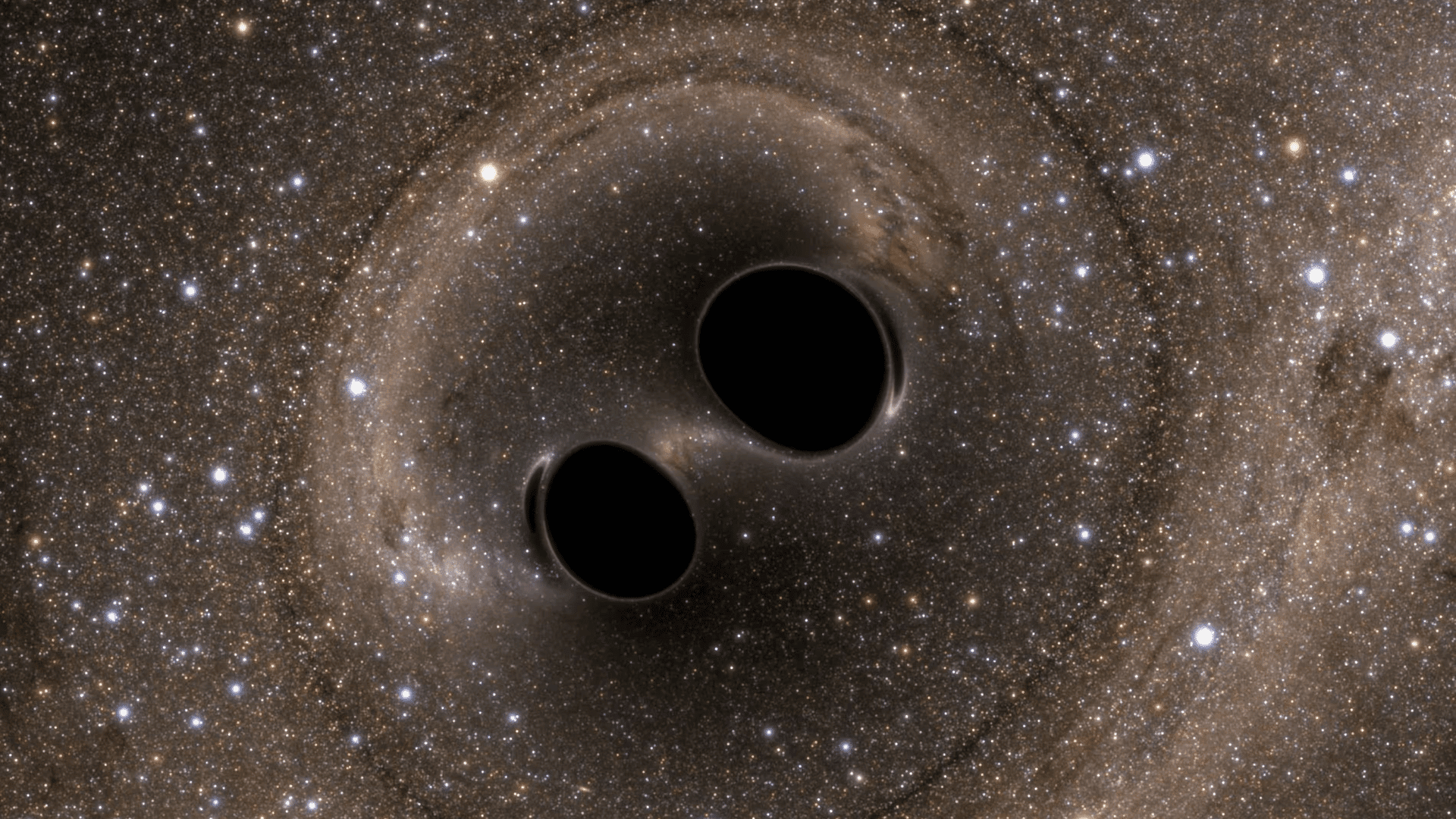

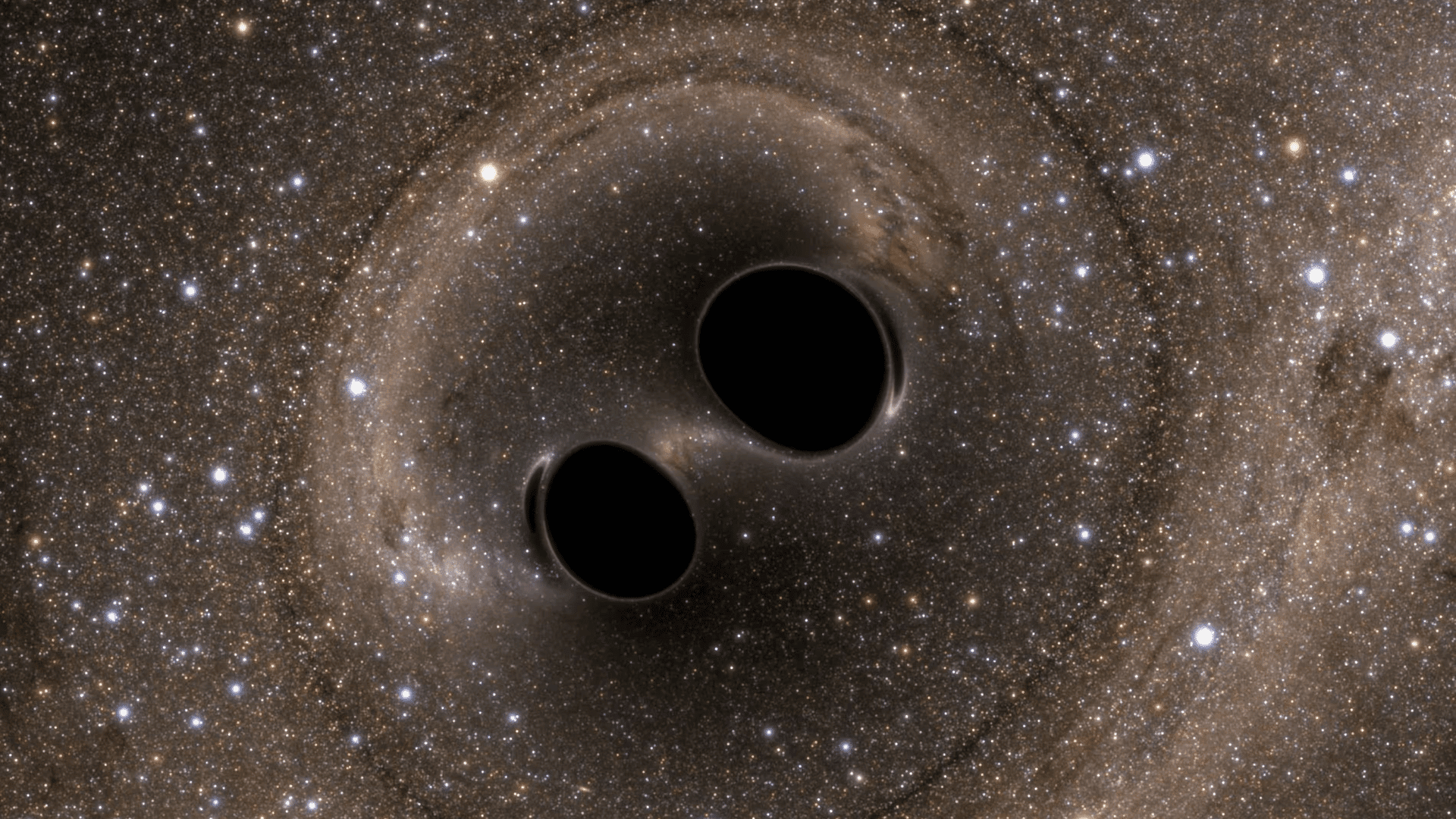

Scientists have detected the largest known black hole merger, which could help us learn more about the rarest type of black hole in the universe.

Largest Black Hole Merger

The new collision was discovered by the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA (LVK) Collaboration, a group of four detectors that use gravitational waves to identify cataclysmic cosmic events. The merger, which took place on the outer rim of the Milky Way galaxy, produced a black hole roughly 225 times more massive than the Sun.

The masses of the two black holes are approximately 100 and 140 times that of the Sun. Black holes of these sizes fall within a “mass gap” that challenges conventional ideas of how they form.

Advertisement

“We expect most black holes to form when stars die — if the star is massive enough, it collapses to a black hole,” Mark Hannam, a physics professor at Cardiff University in Wales and a member of the LVK Collaboration, told Live Science. “But for really massive stars, our theories say that the collapse is unstable, and most of the mass is blasted away in supernova explosions, and a black hole cannot form.”

“We don’t expect black holes to form between about 60 and 130 times the mass of the Sun,” he added. “In this observation, the black holes appear to lie in that mass range.”

All known black holes currently fall into two categories: stellar-mass black holes, which range from a few to a few dozen times the Sun’s mass, and supermassive black holes, which can be anywhere from about 100,000 to 50 billion times as massive as the Sun. Those that fall into a gap between those two mass ranges, known as intermediate-mass black holes, are rare as they’re physically unable to form from direct star collapses.

Astrophysicists have speculated that these types of black holes form from merging with others of a similar size. As technology continues to evolve and advance, scientists hope to discover more mergers of this nature.

“Usually what happens in science is, when you look at the universe in a different way, you discover things you didn’t expect and your whole picture is transformed,” said Hannam to The Guardian. “The detectors we have planned for the next 10 to 15 years will be able to see all the black hole mergers in the universe, and maybe some surprises we didn’t expect.”