According to a new study, there is a thriving coastal ecosystem living in the open ocean in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. The plastic debris patch, which is double the size of Texas, is located between California and Hawaii.

A New Coastal Ecosystem

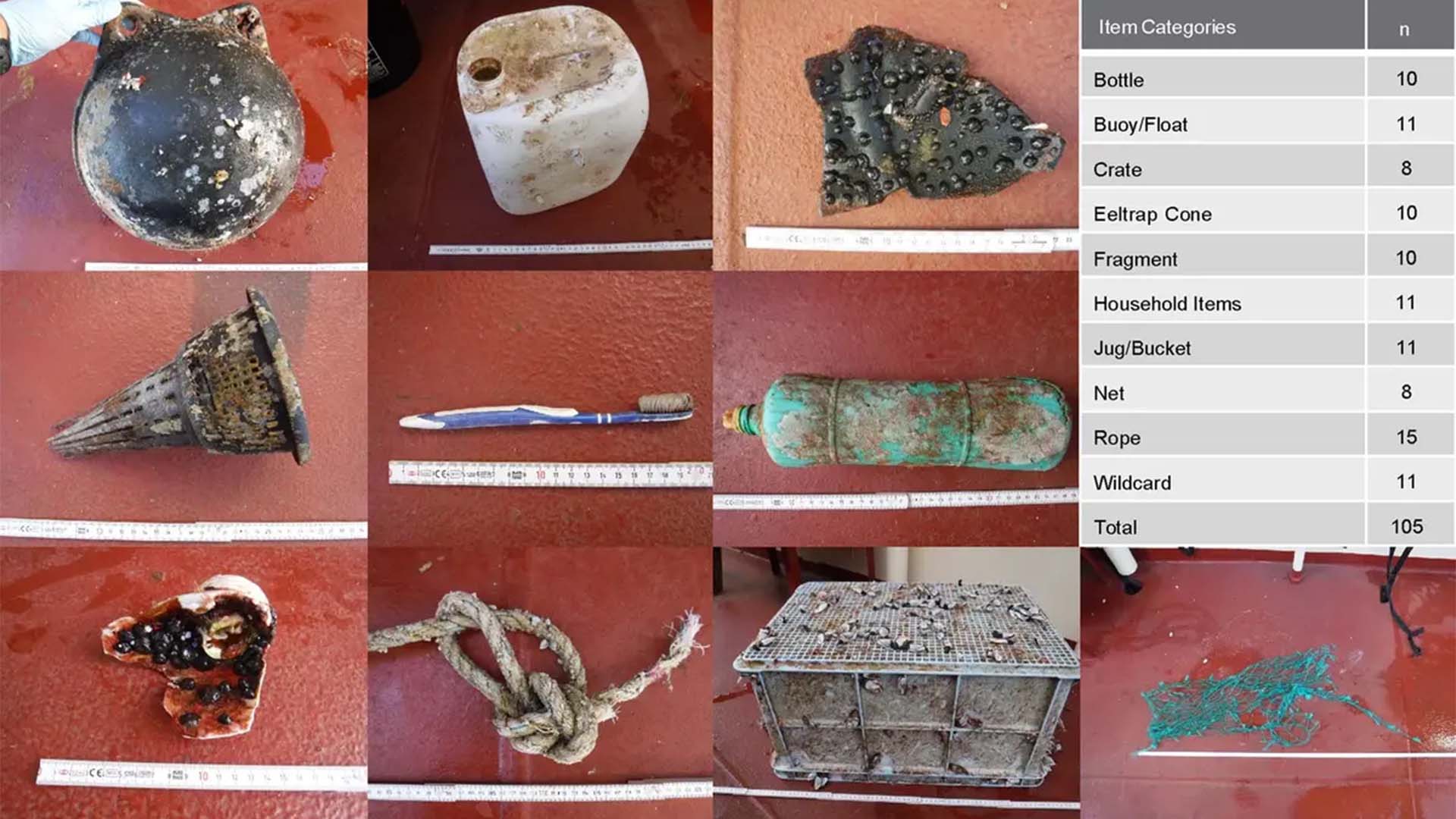

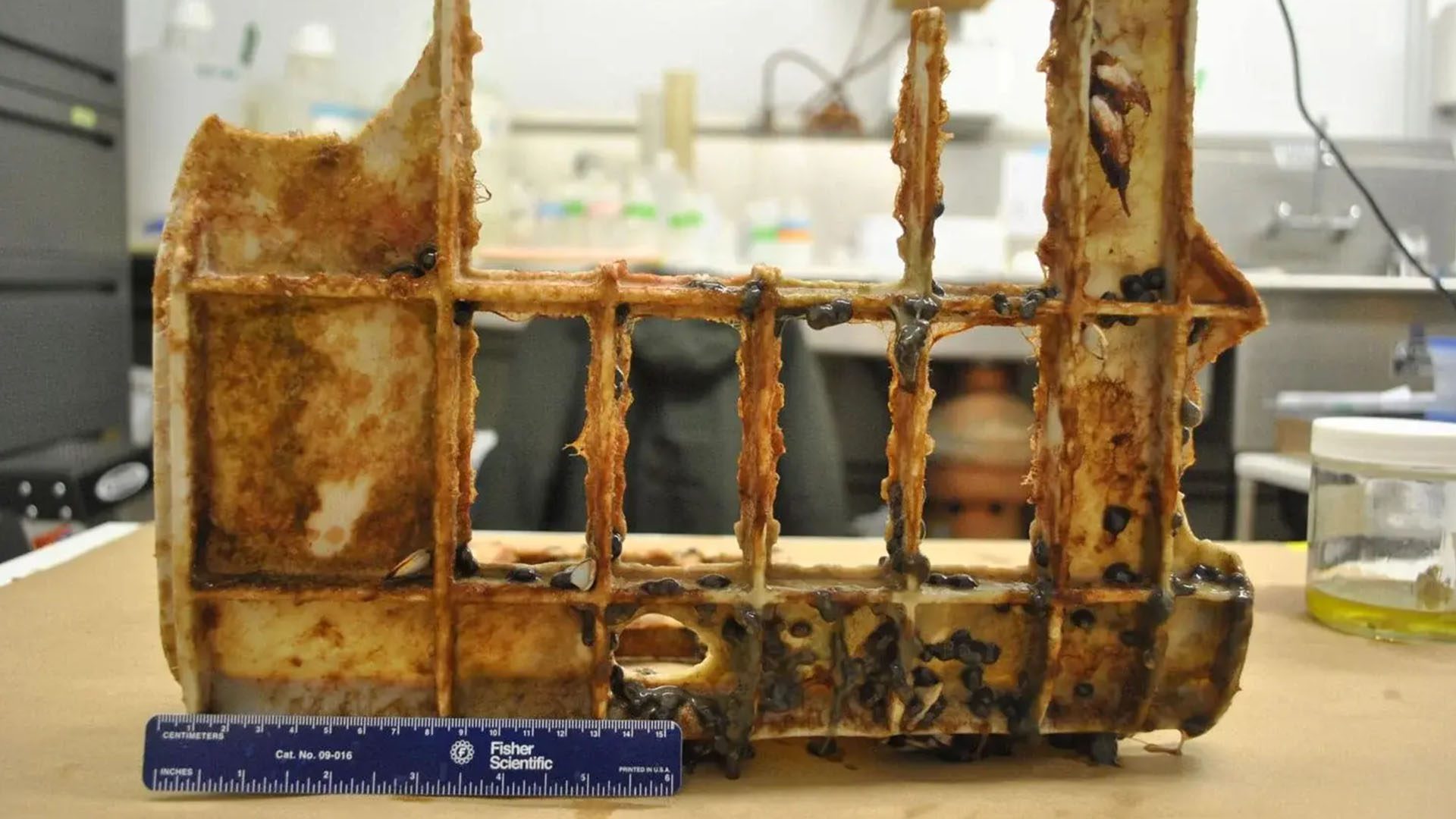

The study, led by the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, was published in the Nature Ecology & Evolution journal in April. For the study, scientists examined 105 pieces of debris that were collected between November 2018 and January 2019. The plastic debris included fishing nets, ropes, and bottles.

The researchers identified 584 marine invertebrate organisms on the debris, accounting for 46 different species. Interestingly, 80 percent of the species found belong to coastal habitats, not the open ocean. These coastal species were found thriving, surviving, and reproducing in the open ocean, even though their native homes were thousands of miles away.

A likely explanation for this new ecosystem is the fact that plastic pollution debris can float in the oceans for years, unlike organic material that decomposes and sinks within a few months. This enables coastal creatures that are not normally able to survive in the open ocean to create new floating ecosystems. As the research paper notes, “Our results demonstrate that the oceanic environment and floating plastic habitat are clearly hospitable to coastal species. Coastal species with an array of life history traits can survive, reproduce, and have complex population and community structures in the open ocean.”

With plastic pollution waste generation expected to exponentially increase in the next few decades, the scientists of the study predict that similar new ecosystems will increasingly be created. However, further research is needed to fully evaluate the consequences of the introduction of new species into remote areas of the ocean.

As Linsey Haram, the study’s lead author, explained to CNN, “There’s likely competition for space, because space is at a premium in the open ocean, there’s likely competition for food resources – but they may also be eating each other. It’s hard to know exactly what’s going on, but we have seen evidence of some of the coastal anemones eating open ocean species, so we know there is some predation going on between the two communities.”

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch

At 620,000 square miles, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is the largest accumulation of ocean plastic in the world. The Ocean Cleanup, a non-profit organization dedicated to developing and scaling technologies to rid the oceans of plastic, estimates that there are about 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic in the patch, weighing an estimated 80,000 tonnes. The majority of the plastic comes from the fishing industry, and between 10% and 20% of its total volume can be traced back to the 2011 tsunami in Japan.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch and other large garbage patches across the oceans form because of one of the five major gyres. A gyre is a large system of rotating ocean currents that pulls trash toward its center and traps it there. Once these plastics enter the gyre, they are unlikely to leave the area until they degrade into smaller microplastics. And, as The Ocean Cleanup notes, as more plastics are discarded into the environment, microplastic concentration in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch will only continue to increase.