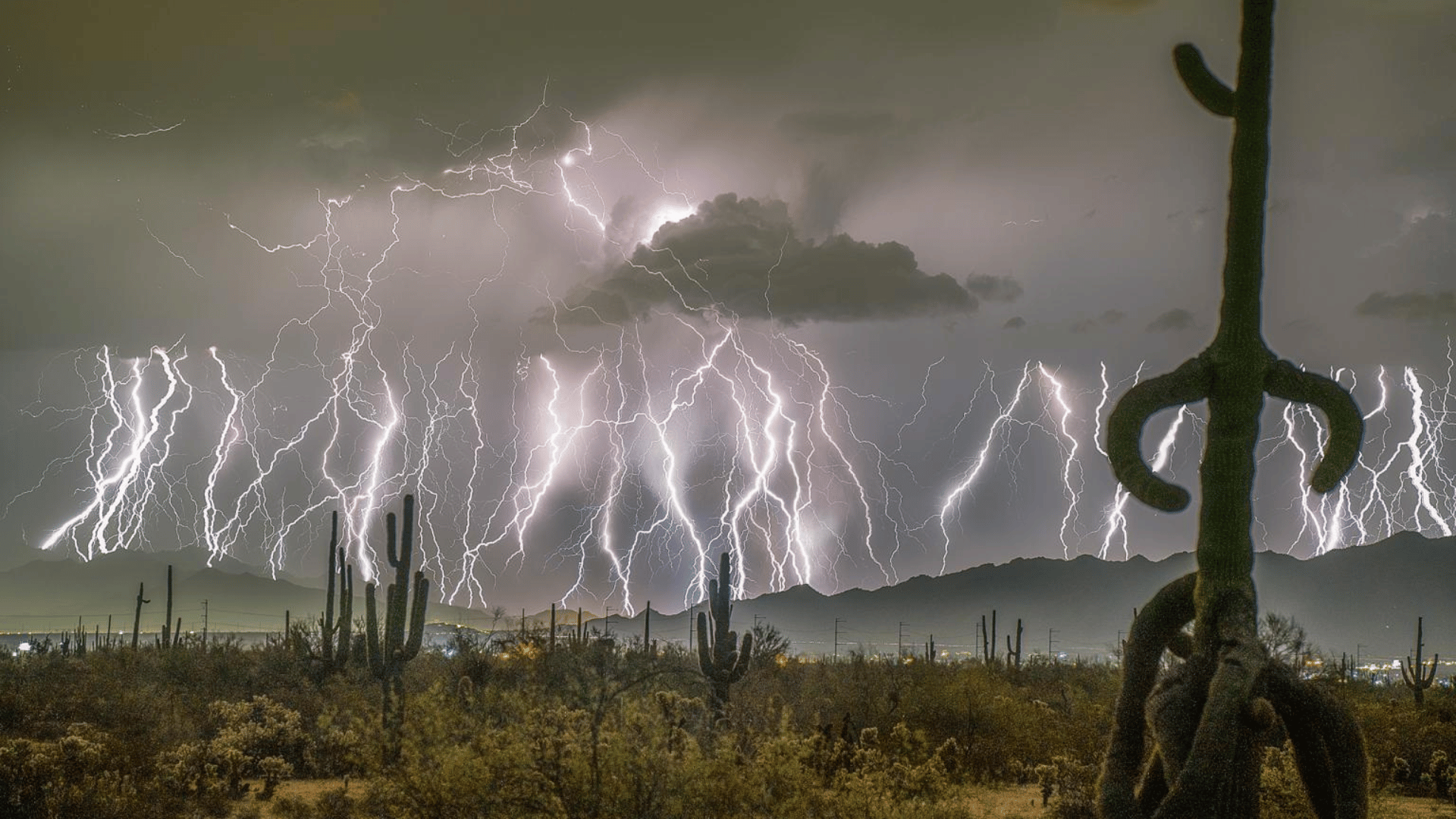

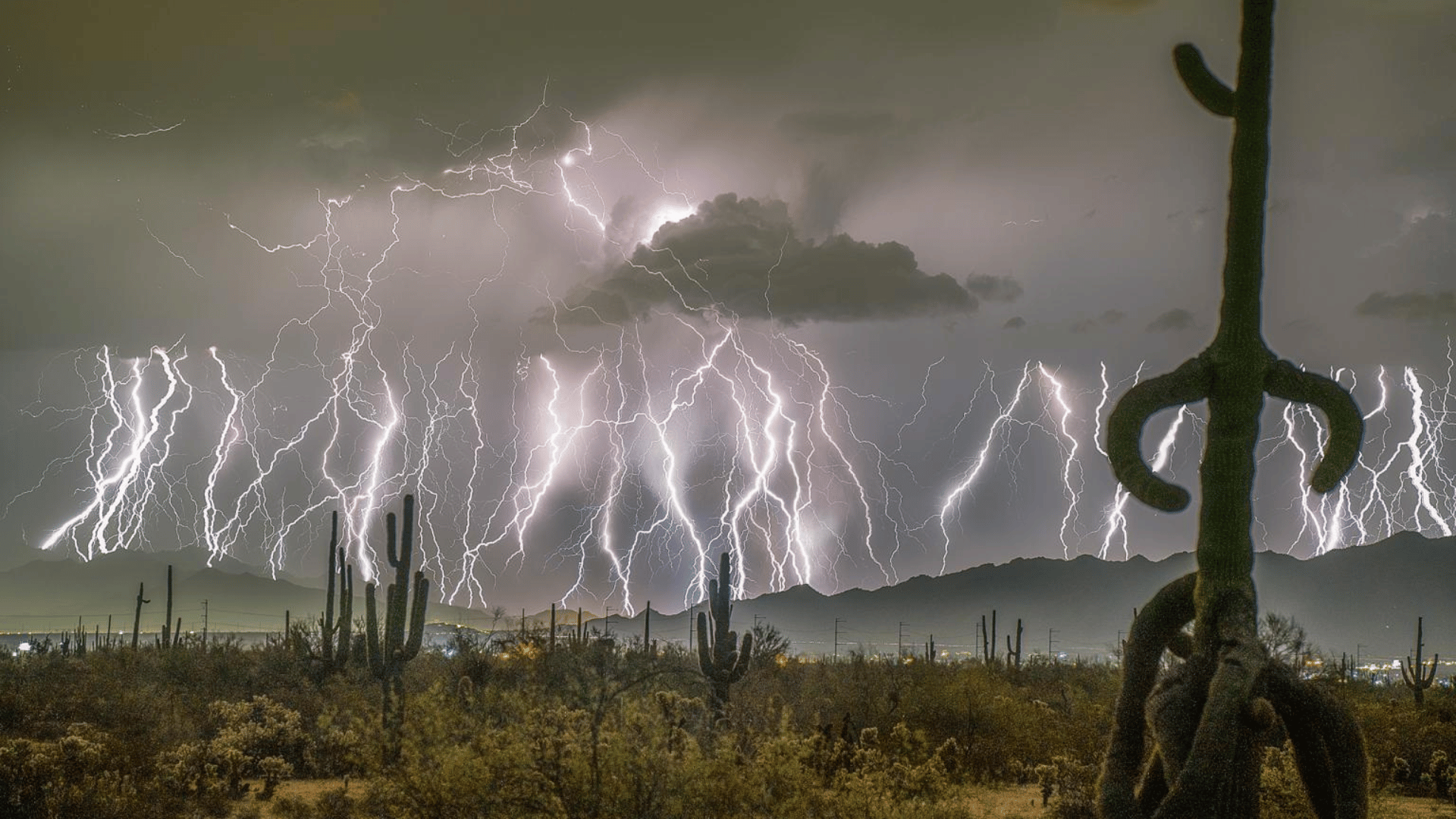

A new study in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society discovered and measured the length of a record-breaking “megaflash” lightning bolt.

Record-Breaking Megaflash Lightning Bolt

The bolt, which sparked from Texas to Kansas City, Missouri, traveled 515 miles in seconds. Researchers discovered the megaflash while examining satellite data with new computational methods.

“We call it megaflash lightning and we’re just now figuring out the mechanics of how and why it occurs,” stated Randy Cerveny, one of the study’s authors and a professor of geographical sciences at Arizona State University, according to CNN.

Lightning occurs when ice and water particles collide and exchange electrons in a thunderstorm, creating a buildup of electrical charge that becomes too strong for the atmosphere to hold. When lightning travels more than 60 miles from where the storm originated, it’s considered a megaflash.

Advertisement

“Flashes at this extreme scale always existed, and are now becoming identifiable as our detection capabilities and data processing methods improve,” the paper says.

As a megaflash travels through clouds, it is capable of emitting multiple ground-striking bolts. Fewer than 1% of thunderstorms produce megaflashes, according to satellite data analyzed for the study.

“You might have an entire thunderstorm’s worth of lightning, cloud-to-ground strokes, in one flash,” stated Michael Peterson, the report’s lead author and a senior scientist at Georgia Institute of Technology’s Severe Storms Research Center.

Studying these types of phenomena could help scientists and forecasters better understand the capabilities of lightning to prepare for extreme events. It may also allow them to better determine what specific set of conditions allows megaflashes to form.

As they continue to analyze data, satellite-based lightning mappers expect to find more record-breaking bolts.

“What I’m looking forward to is seeing how does the location of where lightning occurs change?” said Chris Vagasky, a meteorologist with the National Lightning Safety Council who was not involved in the study. “It is going to be really useful from having all of these datasets, ground-based or satellite-based, to help us really understand what is going on with lightning and thunderstorms.”