A new study may indicate that ancient hunter-gatherers in South America kept foxes as pets before domestic dogs arrived on the continent.

Historically, young wild canid species were commonly adopted by Amazonian indigenous communities where they were treated as part of the family and given burials like humans when they died.

It’s also speculated the foxes held significant symbolic roles within ancient South American societies, which could be indicated by their frequent presence at archaeological sites. For example, teeth belonging to canid species such as Lycalopex sechurae, L. culpaeus, Lycalopex gymnocercus, and Ch. brachyurus were used as personal ornaments and discovered in human burials from Argentina and Peru.

At a 1,500-year-old burial site in Patagonia, Argentina, a human skeleton was found buried alongside a fox. This could suggest the pair may have shared a bond similar to that of a human and a dog during their lifetimes.

The archaeological site of Cañada Seca, discovered in 1991, contains the remains of approximately 24 members of the hunter-gatherer community. The site contained a total of 3,470 human bones belonging to 3 infants, 1 child, 2 adolescents, and 18 adults.

Researchers identified the bones of an unknown canid within one of the burial pits, though the relationship between the animal and human has remained a mystery.

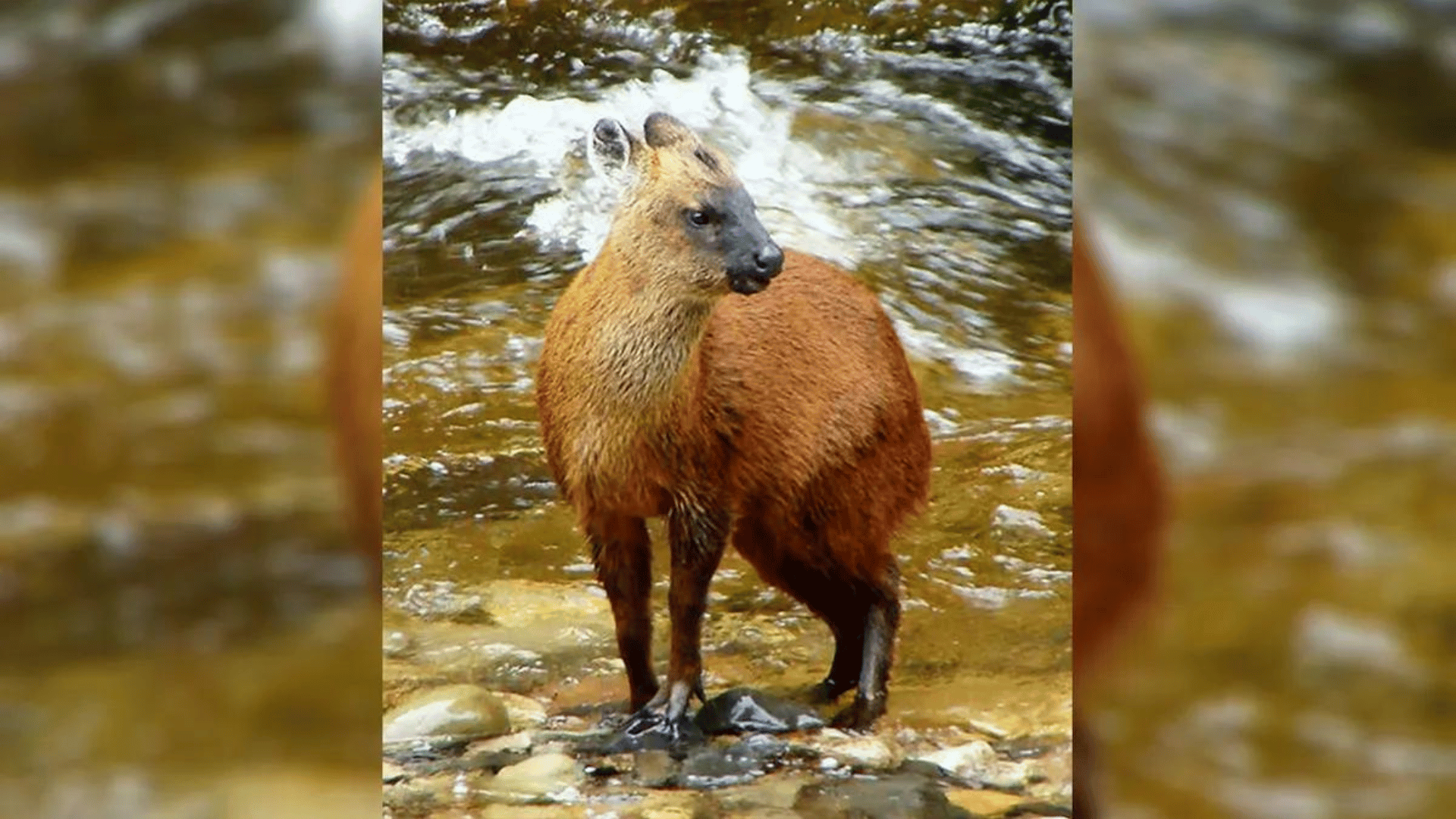

The authors of a new study conducted an extensive genetic, morphological, and isotopic analysis of the ancient bones. This allowed them to discover that the fox belonged to an extinct species known as Dusicyon avus, which roamed South America until around 500 years ago, and not a gray fox, as had previously been speculated.

The study results have also given researchers new insights regarding the social context of the pairing, as it was previously difficult to interpret the peculiar burial arrangements. By studying the carbon and nitrogen isotopes in the fox bones, the authors confirmed that the animal survived on a human-like diet that contained more vegetation and less meat than a wild fox would typically consume.

This “systematic feeding” has allowed the researchers to surmise that the fox was likely a pet or companion of the hunter-gatherers during this period. This idea is further supported by previous radiocarbon dating of the animal’s bones, which showed that the fox was buried around the same time as the human.

Explore Tomorrow's World from your inbox

Get the latest science, technology, and sustainability content delivered to your inbox.

I understand that by providing my email address, I agree to receive emails from Tomorrow's World Today. I understand that I may opt out of receiving such communications at any time.

“Its strong bond with human individuals during its life would have been the primary factor for its placement as a grave good after the death of its owners or the people with whom it interacted,” stated the study authors.

In addition to determining the relationship between the pair, the study authors attempted to discover the cause of the canid’s extinction. One hypothesis states that the species may have bred with domestic dogs, thus resulting in a hybrid lineage that eventually genetically assimilated into the dog bloodline.

This may prove incorrect, however, as the genetic differences between D. avus and modern dogs are significant enough that they may not have been capable of producing viable offspring. Another possible theory suggests that the species went extinct as the result of a combination of climate change and human interference.