Nuclear power has a storage problem. For decades, the U.S. has been tucking away used fuel rods once they’ve spent about five years in a reactor. However, the “spent” rods actually still hold about 95% of their energy. Instead of letting that potential sit in a cooling pool or a concrete cask, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) is looking for a way to put it back to work.

The DOE recently put $19 million toward this goal, awarding funds to five American companies. The plan is to develop better ways to recycle that fuel. If these projects succeed, they could shrink the volume of nuclear waste by 90% and make the U.S. less dependent on foreign uranium.

“Used nuclear fuel is an incredible untapped resource in the United States,” said Assistant Secretary for Nuclear Energy Ted Garrish.

New Ideas for Old Nuclear Fuel

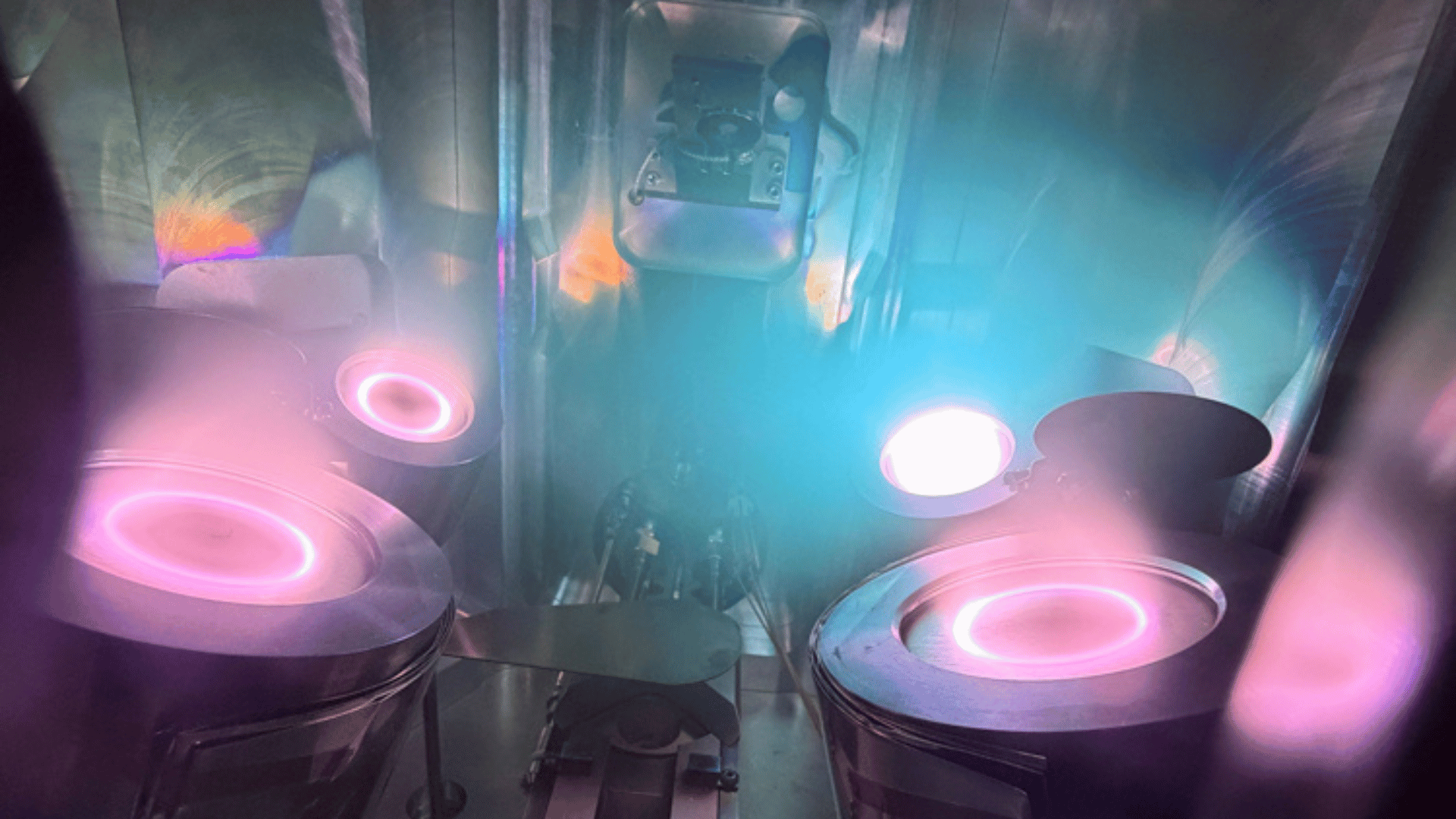

The five companies getting to work are Alpha Nur, Curio Solutions, Flibe Energy, Oklo, and Shine Technologies. All five of the companies are tackling different parts of the project. Some are focused on turning old fuel into gas, while others are looking at using molten salts or electrochemical methods to pull out the good stuff.

For example, Alpha Nur is working on a way to take fuel from research reactors and turn it into a specific type of uranium needed for the next generation of small modular reactors. Meanwhile, Shine Technologies is trying to figure out how to handle the whole lifecycle, from transport to disposal.

It isn’t just about power, either. Recycling these materials can also help us recover rare isotopes used in hospitals for medical imaging and cancer treatments.

The Road Ahead

These projects will run for about three years and will have to cover at least 20% of the costs themselves. While there are still big hurdles to clear, like making the tech affordable and ensuring it stays secure, the hope is that these advancements will eventually lead to a self-sustaining domestic fuel cycle.