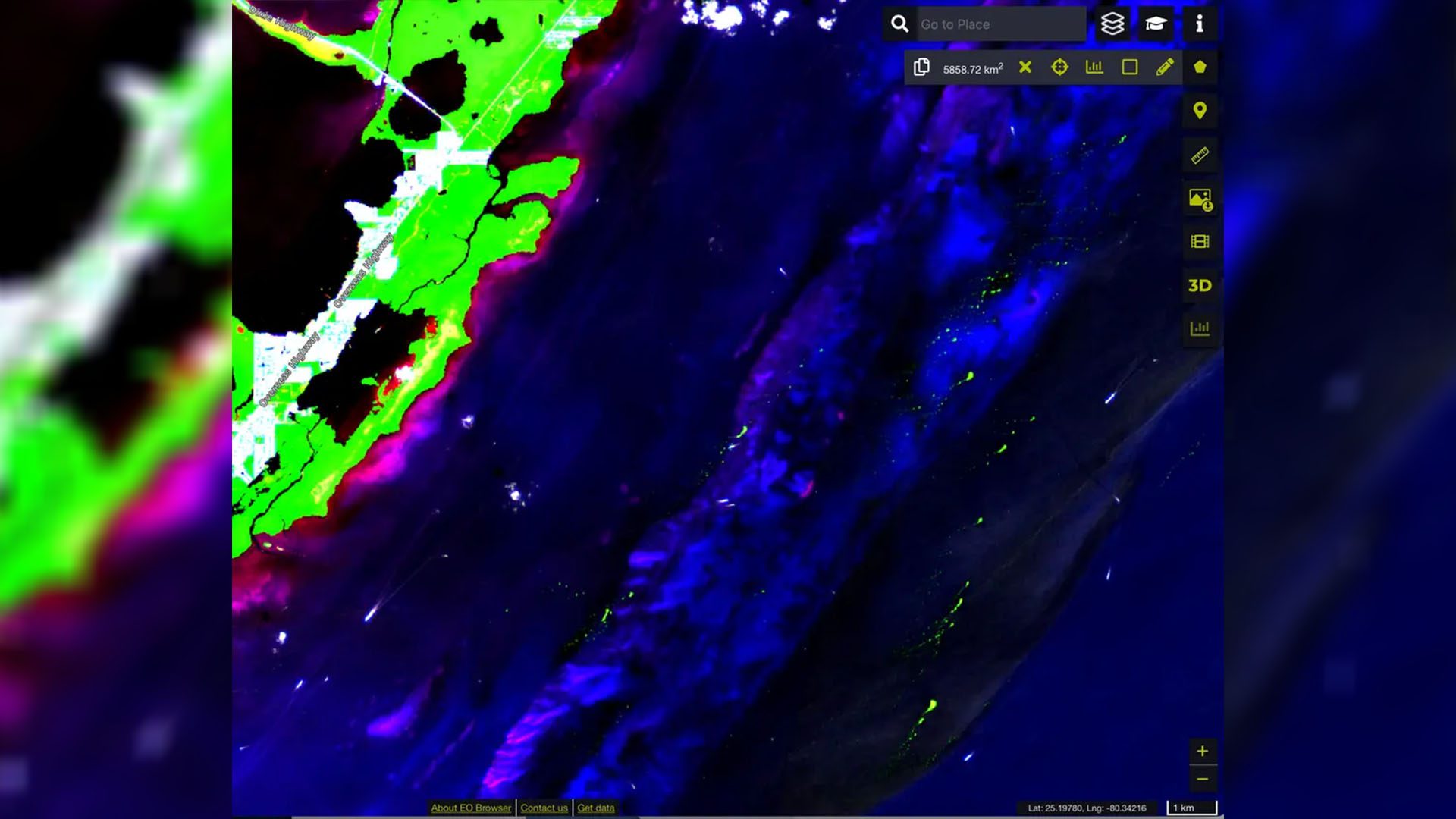

In July, a 5,000-mile mass of seaweed that formed in the Atlantic Ocean will hit Florida and other coastlines throughout the Gulf of Mexico. Known as the “Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt,” the biomass contains scattered patches of seaweed on the open sea. This year’s mass could be one of the biggest on record, with some experts predicting that seaweed could pile up on beaches up to 5 or 6 feet deep.

The seaweed is classified as sargassum, which is a genus of large brown algae that includes over 300 species. In the sea, sargassum is beneficial and harmless. The floating habitat provides food and protection for many fishes, mammals, marine birds, and more. It is also a nursery area for many commercially important fishes such as mahi-mahi and amberjacks.

However, when the floating sargassum began to wash ashore in coastal communities around the Atlantic in 2011, the issues associated with sargassum began. When onshore, the algae begins to rot and releases the toxic and smelly gas hydrogen sulfide, which attracts flies and causes respiratory problems. The seaweed itself also contains arsenic in its flesh, making it dangerous if ingested or used for fertilizer.

Additionally, the seaweed can also harm coastal marine ecosystems and disrupt recreation and fishing. For hotels and beach towns, the seaweed deters tourists and is very difficult to remove from the beach.

Because scientists began closely monitoring sargassum in 2011, the cause of the phenomenon is still widely unknown. Some experts point to warmer waters helping the seaweed grow faster, as well as changes in wind patterns, sea currents, rainfall, and drought. Mike Parsons, a professor of marine science at Florida Gulf Coast University, explained, “We do know that to get a lot of seaweed, you need nutrients, and you need sunlight. Of course, as you get close to the equator, there’s going to be more sunlight.”

Thousands of tons of Sargassum have ended up on beaches in the Caribbean, Americas, and West Africa to date. In 2022, for example, the U.S. Virgin Islands declared a state of emergency, after “unusually high amounts” of sargassum piled up on its shores and affected a desalination plant on St. Croix.

This year is estimated to be worse than usual because the bloom started so early. In previous years, the algae blooms in the spring and summer, but a great deal of sargassum already started piling up this winter. In January, scientists measured the largest bloom for that month on record.