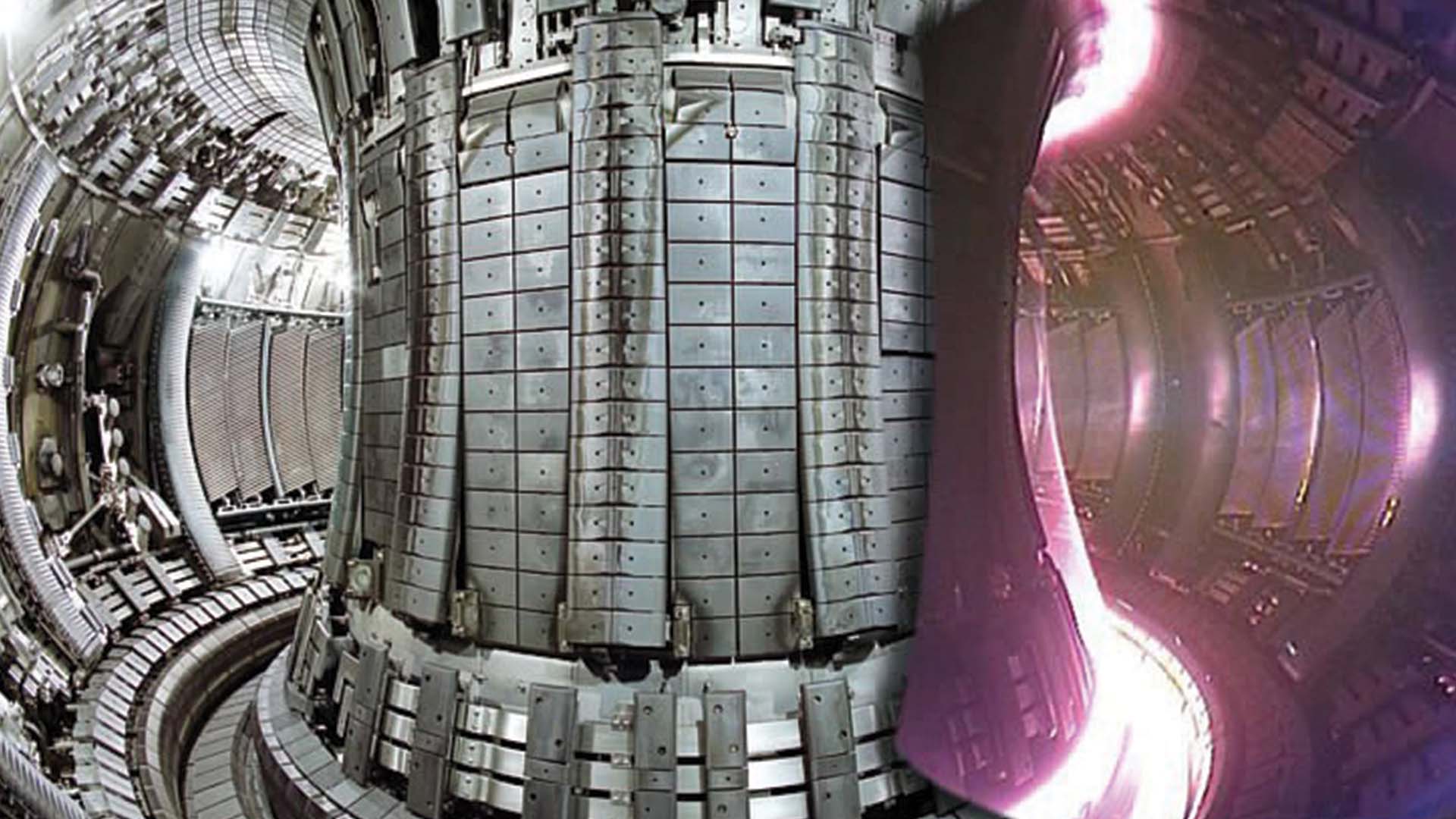

In February 2022, scientists and engineers in the United Kingdom announced that they made a record-breaking milestone in producing nuclear fusion energy. At the Joint European Torus (JET) facility near Oxford, a team generated 59 megajoules of sustained energy for five seconds. This is more than double the 1997 record, and it is enough energy to power 35,000 homes during the five seconds.

🥳Record-breaking 59 megajoules of sustained fusion energy at world-leading UKAEA’s Joint European Torus (JET) facility. Video shows the record pulse in action. Full story https://t.co/iShCGwlV9Y #FusionIsComing #FusionEnergy #STEM #fusion @FusionInCloseUp @iterorg @beisgovuk pic.twitter.com/ancKMaY1V2

— UK Atomic Energy Authority (@UKAEAofficial) February 9, 2022

The team produced the energy in a tokamak machine where .1 milligrams of both deuterium and tritium, isotopes of hydrogen, were heated to temperatures ten times hotter than the center of the sun to create plasma. The isotopes are held in place with superconductor electromagnets as they spin around, fuse, and release the energy as heat. Deuterium is freely available in seawater, and tritium can be harvested as a by-product of nuclear fission.

According to the UK Atomic Energy Authority, this fusion experiment clearly demonstrates “…the potential for fusion energy to deliver safe and sustainable low-carbon energy,”. A fusion reaction is about four million times more energetic than a chemical reaction, such as burning coal, oil, or gas, which would be monumental for reaching the worldwide goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

Fusion’s only by-product is helium plus an energetic neutron, meaning that it has no radioactive waste. Fusion reactors are also expected to have a much lower risk for nuclear proliferation in comparison to current nuclear reactors, and there is no risk of runaway reactions.

However, creating nuclear fusion on earth is one of scientists’ and engineers’ greatest challenges. In order to fuse, hydrogen atoms need to be both extremely hot and packed together tightly enough and long enough to collide frequently. This means that a fusion power plant requires developing materials that will withstand extreme environments, getting the plasma to sustain itself without external heating, transferring power efficiently, and creating tritium for fuel. In other words, sustaining nuclear fusion is no easy feat.

The data from JET’s record-shattering fusion experiment will help ITER, the world’s largest nuclear fusion project which is currently being built in Southern France. ITER’s goal is to demonstrate the scientific and technological feasibility of fusion, and it is a collaboration between seven members: China, the European Union, India, Japan, South Korea, Russia, and the United States.

ITER is expected to come online as soon as 2025 with a prototype fusion power plant being ready by 2050. ITER is larger and more advanced than JET which will allow the process to be sustained for longer—JET could only last for five seconds because any longer would cause its copper wire magnets to overheat.