Jet engines are incredibly complex, but some of the most important maintenance work still relies on a person getting into those tight spaces. GE Aerospace wants to change that with robotic inspectors in its service shops to handle the tedious work of checking engine parts.

The main focus is on the high-pressure turbine disk. These nickel-based disks spin at high speeds and hold the engine’s blades in place. Because they are so critical, something as simple as a tiny scratch or the slightest bit of corrosion has to be caught. Traditionally, an expert would spend hours physically searching for these minuscule issues.

Robots That “Dance”

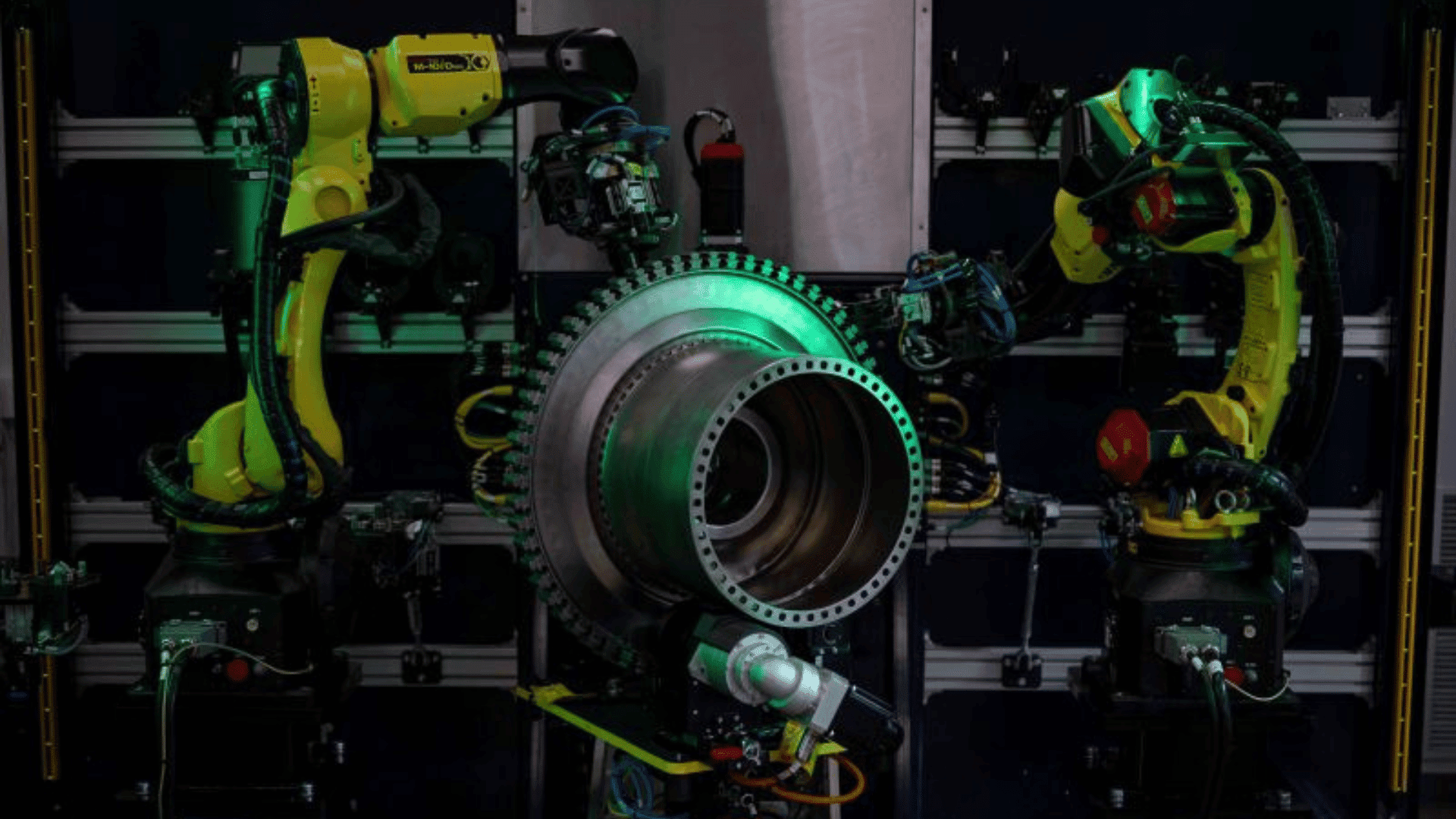

To make this easier, engineers spent five years developing what they call “white light” robot inspectors. In the workshop, two robotic arms move around a turbine disk, using optical scanners to map every millimeter. The team compares their choreographed movement to ballroom dancers.

Sam Blazek, a service technology leader at GE Aerospace, used to inspect parts “caveman style” with a handheld light.

“Staring at the same part or feature for eight to twelve hours a day can make your head hurt,” Blazek said. “You’re constantly twisting your head, eyes, and neck as you try to focus on each individual feature.”

Better Data

These robots create a digital history. They record serial numbers and catalog every tiny dent or crack in the cloud. This helps engineers decide if a part can be fixed or if it needs to be scrapped. The latest version of this tech even uses line-scan cameras to provide a video-like stream that mimics what the human eye sees, but on a much larger monitor.

Additionally, the bots free up the humans to do the actual thinking. An inspector can start the robot and walk away to handle another task.

“The goal is to mount a part for inspection, hit ‘go,’ let the system run while you go do another job, and come back to monitor the inspection on a screen,” Blazek explained. “A person still needs to be there to examine the screen and make the call.

“They just don’t need to physically huddle around the part for hours on end to collect the data. We use their expertise where it’s needed, which is in disposition,” he added.

By automating the repetitive stuff, GE is making the process more accurate and less exhausting. “We’re not trying to replace humans with this technology.” Blazek said. “We want to replicate them. If we can automate some of the ‘easier’ repeatable, predictable aspects of this job, it frees our inspectors to focus on the technical issues that truly need our attention.”