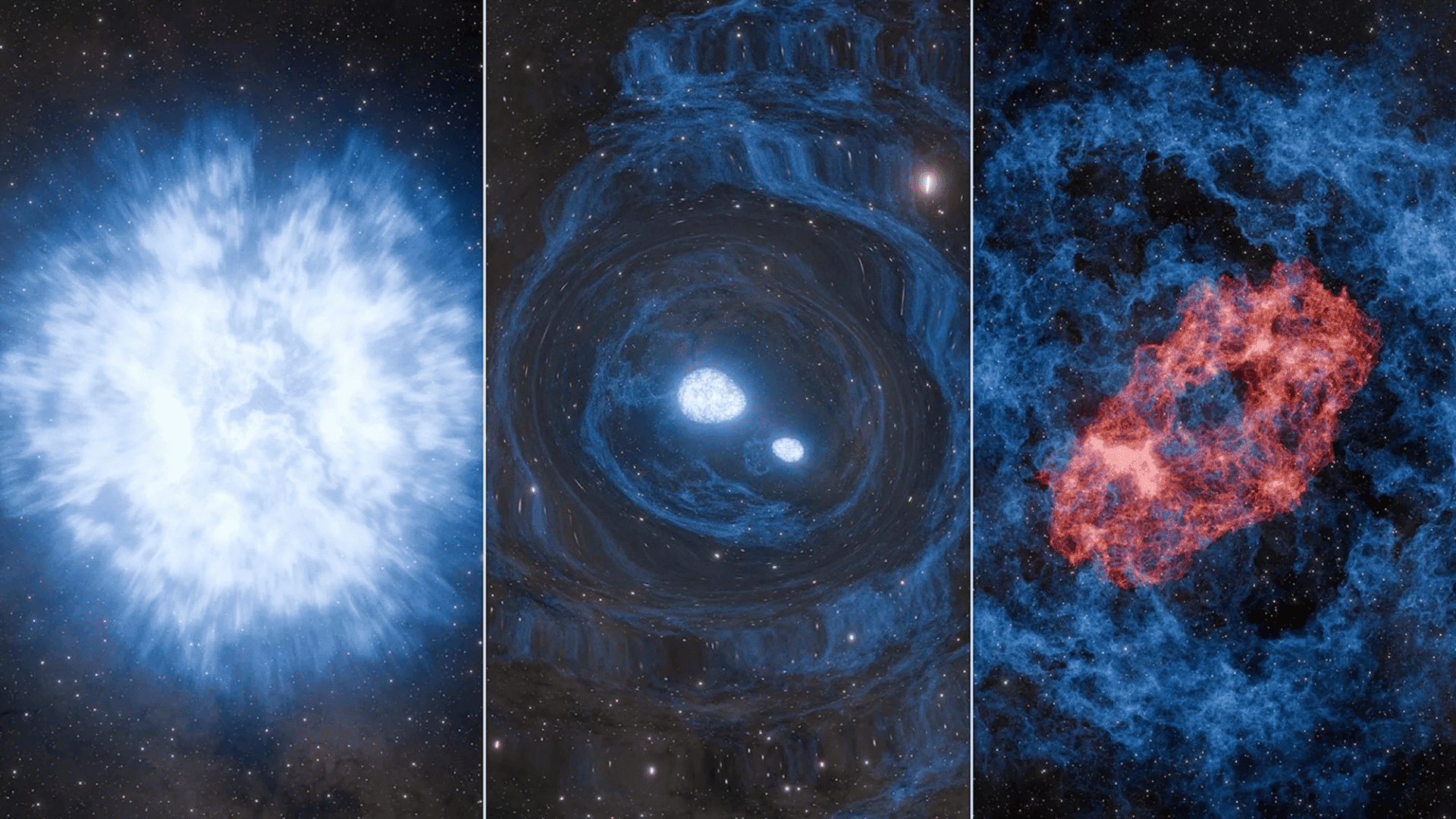

Northwestern University scientists have built a new way to study spinal cord injuries without needing a human patient or an animal. They grew “organoids,” essentially tiny, simplified versions of a human spinal cord, to see how the body reacts to trauma and, more importantly, how to fix it.

These lab-grown models are only a few millimeters wide, but they’re complex. They include neurons and immune cells that react to injury just like a real person’s body would. This allowed the team to simulate car accidents or falls by damaging the organoids and watching as scar tissue formed and cells died.

Testing Spinal Cord Treatment

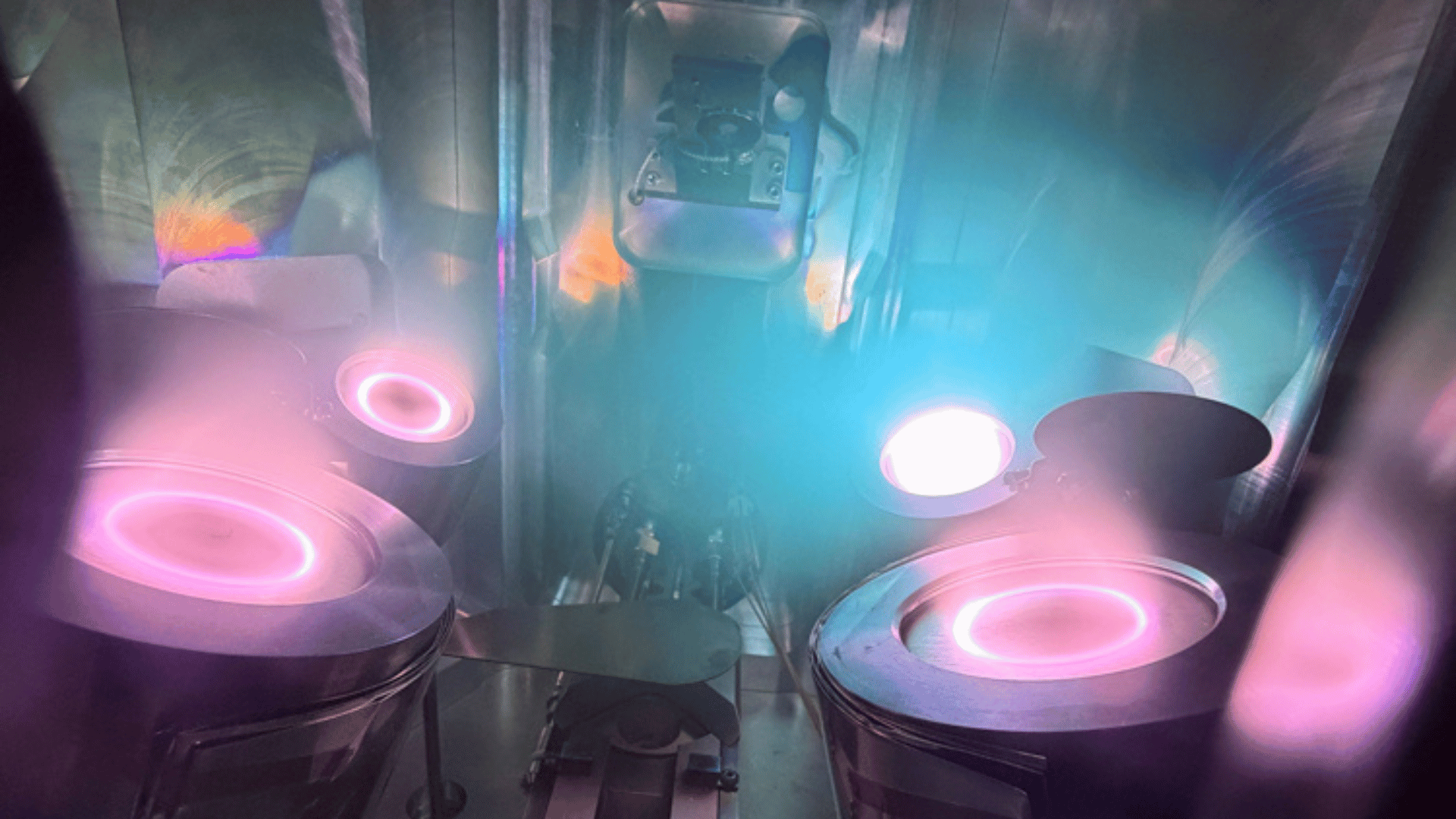

The researchers used these tiny models to test a new treatment called “dancing molecules.” This therapy is made of thousands of molecules that move around rapidly. Because the receptors on our cells are always moving, these “dancing” molecules are much more likely to bump into them and tell the body to start repairing itself.

When the team applied the treatment to the injured organoids, the results were hard to miss. The thick scar tissue that usually blocks healing began to fade, and the nerve cells started growing long extensions to reconnect with one another.

“One of the most exciting aspects of organoids is that we can use them to test new therapies in human tissue. Short of a clinical trial, it’s the only way you can achieve this objective,” Samuel I. Stupp, the lead researcher, explained. “We decided to develop two different injury models in a human spinal cord organoid and test our therapy to see if the results resembled what we previously saw in the animal model.

“After applying our therapy, the glial scar faded significantly to become barely detectable, and we saw neurites growing, resembling the axon regeneration we saw in animals,” Stupp added. “This is validation that our therapy has a good chance of working in humans.”

What’s Next?

The success of this study is a big deal because the FDA has already given this therapy an “Orphan Drug” status. The team now wants to create organoids that model older, chronic injuries to see if they can break through even tougher scar tissue.

Eventually, this tech might lead to personalized medicine where doctors use a patient’s own cells to grow tissue for repairs, making it much safer for the body to accept.