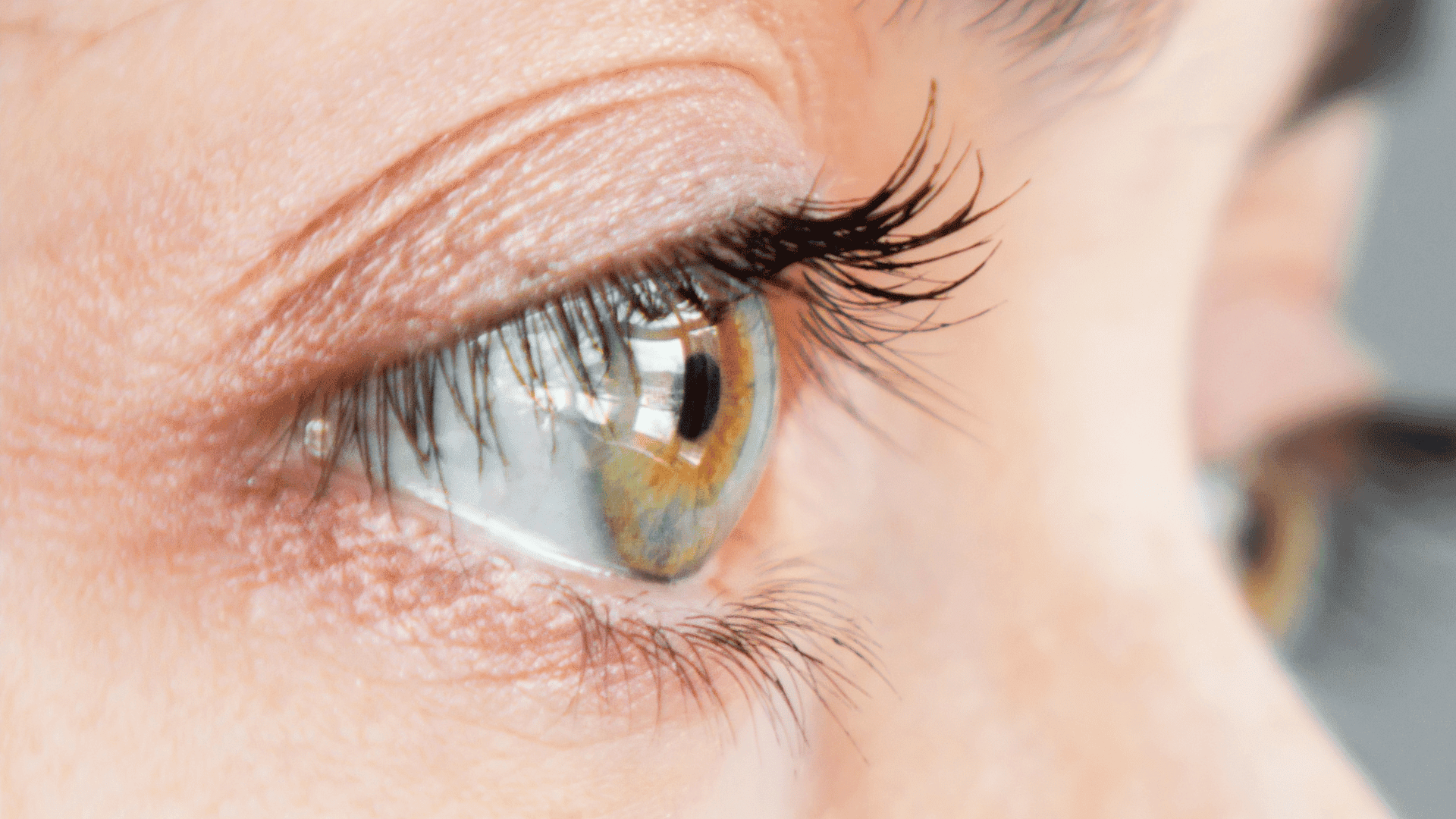

Scientists at Johns Hopkins University have figured out how the human eye develops the sharp, high-definition vision we use every day. By using lab-grown clusters of retinal tissue called organoids, the team discovered that a derivative of vitamin A and thyroid hormones work together to “color in” our sight during early development.

The study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, focuses on the foveola. This tiny spot in the center of the retina is responsible for about 50% of what we see. It’s packed with red and green cone cells that handle daylight and fine detail. However, it lacks blue cones. For a long time, researchers weren’t sure why.

Changing Cell Growth

The old theory was that blue cones simply moved out of the way as the eye grew. However, this new data suggests that the cells actually change their identity. Between weeks 10 and 14 of development, retinoic acid (from vitamin A) and thyroid hormones signal the blue cones in the center of the eye to convert into red or green ones.

“The main model in the field from about 30 years ago was that somehow the few blue cones you get in that region just move out of the way,” said Robert J. Johnston Jr., an associate professor of biology at Johns Hopkins. “We can’t really rule that out yet, but our data supports a different model. These cells actually convert over time, which is really surprising.”

Johnston noted that this process is vital for clear sight. “First, retinoic acid helps set the pattern. Then, thyroid hormone plays a role in converting the leftover cells,” he said. “That’s very important because if you have those blue cones in there, you don’t see as well.”

A New Path For Vision Repair

This discovery matters because the center of the retina is usually the first part to fail in people with age-related vision issues like macular degeneration. Because animals like mice and fish don’t have the same eye structure as humans, these lab-grown organoids are the best way to see what’s actually happening.

“This is a key step toward understanding the inner workings of the center of the retina,” Johnston said. “By better understanding this region and developing organoids that mimic its function, we hope to one day grow and transplant these tissues to restore vision.”

The team hopes this could lead to “made-to-order” cells to replace damaged ones in the eye. It will take more time to ensure these treatments are safe, but the researchers believe it’s a viable path toward helping people see clearly again.