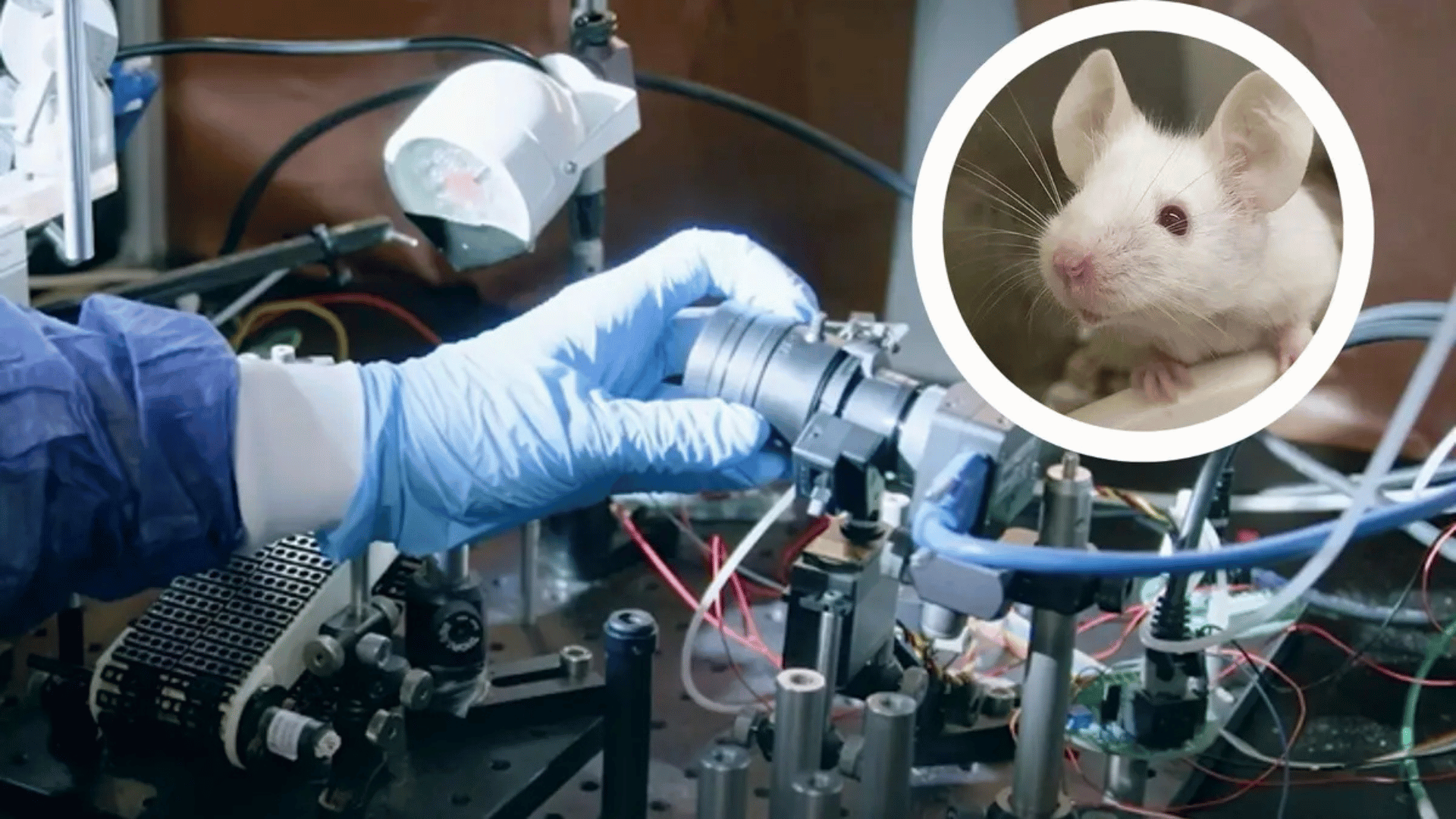

Researchers at the Champalimaud Foundation in Portugal used machine learning to read mice’s facial movements and determine their internal thought strategies. The new study could pave the way for a non-invasive method to study brain activity.

Mind-Reading in Mice

The idea for the study came from an early experiment in which mice were tasked to figure out which of two water spouts elicited a sugary drink. The reward switched between spouts, so the mice needed to adjust their strategy to find the correct one.

“We knew that mice can solve this task using different strategies, and we could identify which strategy they were using according to their behaviour,” said first author Fanny Cazettes, now at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and Aix Marseille University.

Interestingly, though they expected the animals’ neurons to solely reflect their active choice, they found all strategies were represented in the brain simultaneously. This led the team to wonder whether they could discern those strategies through subtle facial movements.

Facial Movements Correspond With Brain Activity

They recorded both facial expressions and brain activity, analyzing the data with machine learning.

“To our surprise, we found that we can get as much information about what the mouse was ‘thinking’ as we could from recording the activity of dozens of neurons,” said Zachary Mainen, a principal investigator at the Champalimaud Foundation.

“Having such easy access to the hidden contents of the mind could provide an important boost to brain research.”

Researchers behind the project were also surprised that facial patterns corresponded with the same strategies in different individuals.

“Similar facial patterns represented the same strategies across different mice,” said co-author Davide Reato, now at Aix Marseille University and Mines Saint-Etienne.

“This suggests that the reflection of specific patterns of thought at the level of facial movement might be stereotyped, much like emotions.”

The study is published in the journal Nature Neuroscience.