Selin Balci’s artwork invites viewers into a hidden world where microbes become storytellers, transforming the smallest life forms into powerful narratives about identity, ecology, and the environment. In this interview with Tomorrow’s World Today, Balci reflects on working with natural elements, why unpredictability has become one of her greatest creative allies, and how her work continues to evolve in tandem with the living organisms that shape it.

Tomorrow’s World Today (TWT): Can you walk us through the process of collecting resources for your art from nature? How do you select the right materials for your work?

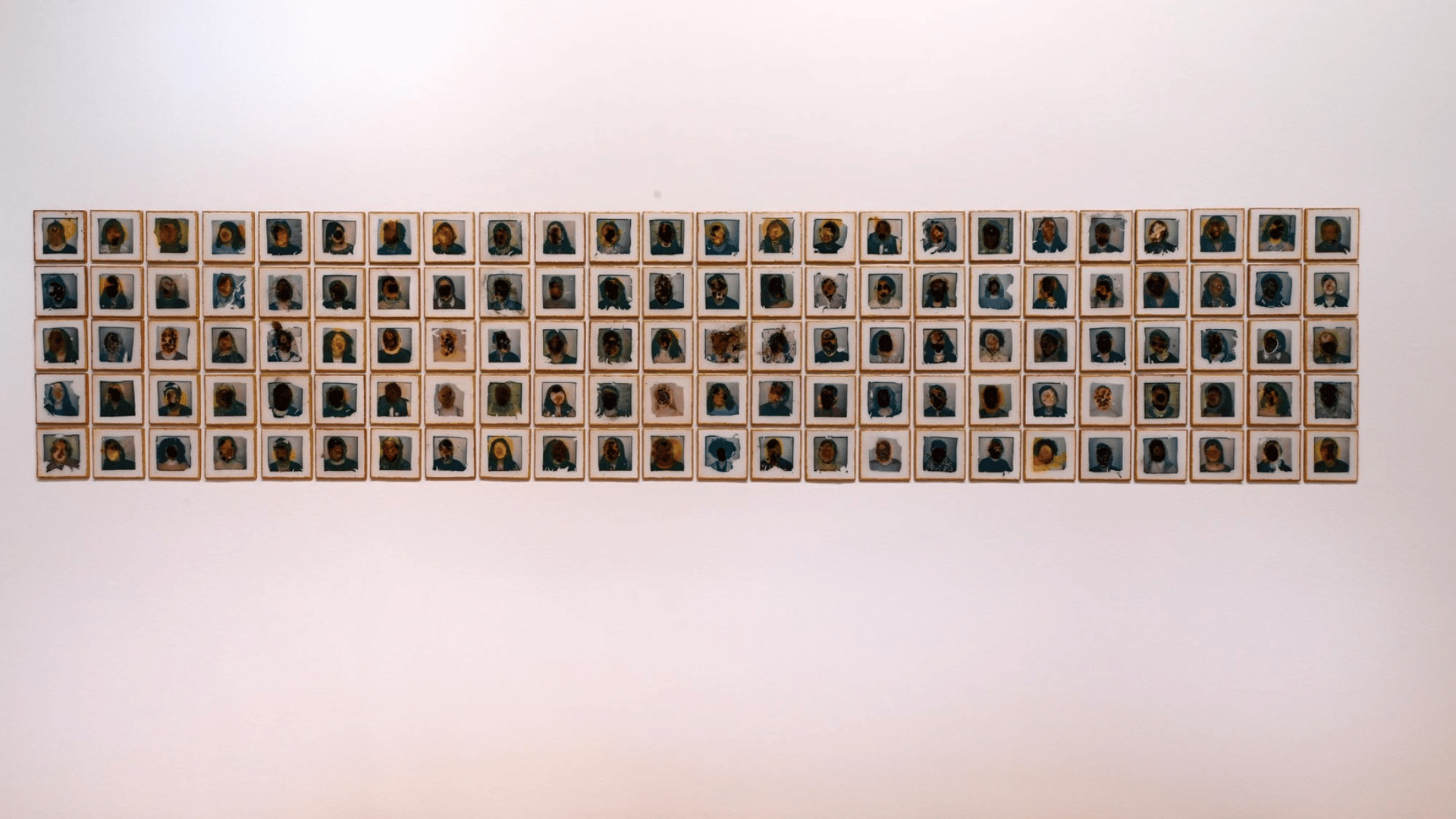

Selin Balci (SB): I often collect spores from environments that carry conceptual significance, such as parks, forests, soil, leaves, and trees, as well as from participants themselves. In projects like Fertile Faces and 30 Faces, I swab volunteers’ skin and cultivate their unique microbial signatures into portraits. In other works, I gather microorganisms from sites tied to environmental questions or historical layers. The selection process is both intuitive and conceptual: I choose organisms and natural materials that already carry the narrative I want to explore.

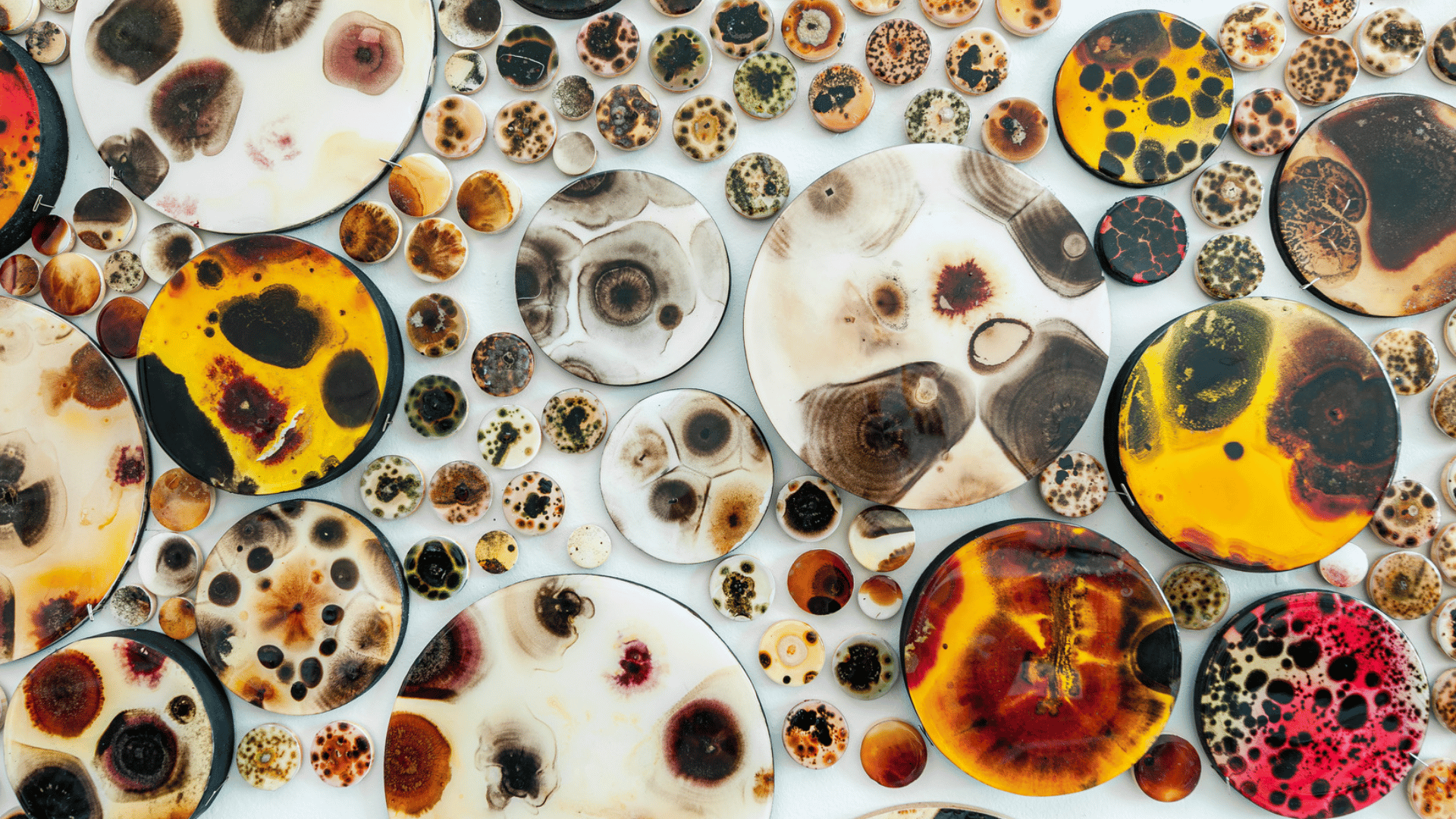

Once collected, I cultivate the spores under controlled conditions and observe how each species behaves, grows, competes, or coexists. These early observations help me lay the foundation for the piece’s visual language. I create a color scheme based on the natural pigments produced by different molds; my palette is limited to yellow, red, purple, orange, green, and black because those are the colors most produced during germination.

After preparing the initial surface and establishing the color environment, I inoculate the material and initiate growth. Because I work in an art studio rather than a sterile laboratory, contamination is always part of the equation. Airborne spores inevitably land on the substrate, find the nutritious surface, and begin expressing themselves with their own colors, shapes, and textures. Instead of fighting them, I’ve learned to embrace these unexpected arrivals. Early in my practice, I tried to eliminate contamination with UV lights and bleach, but I realized I wasn’t trying to make scientific data; I was creating living artwork.

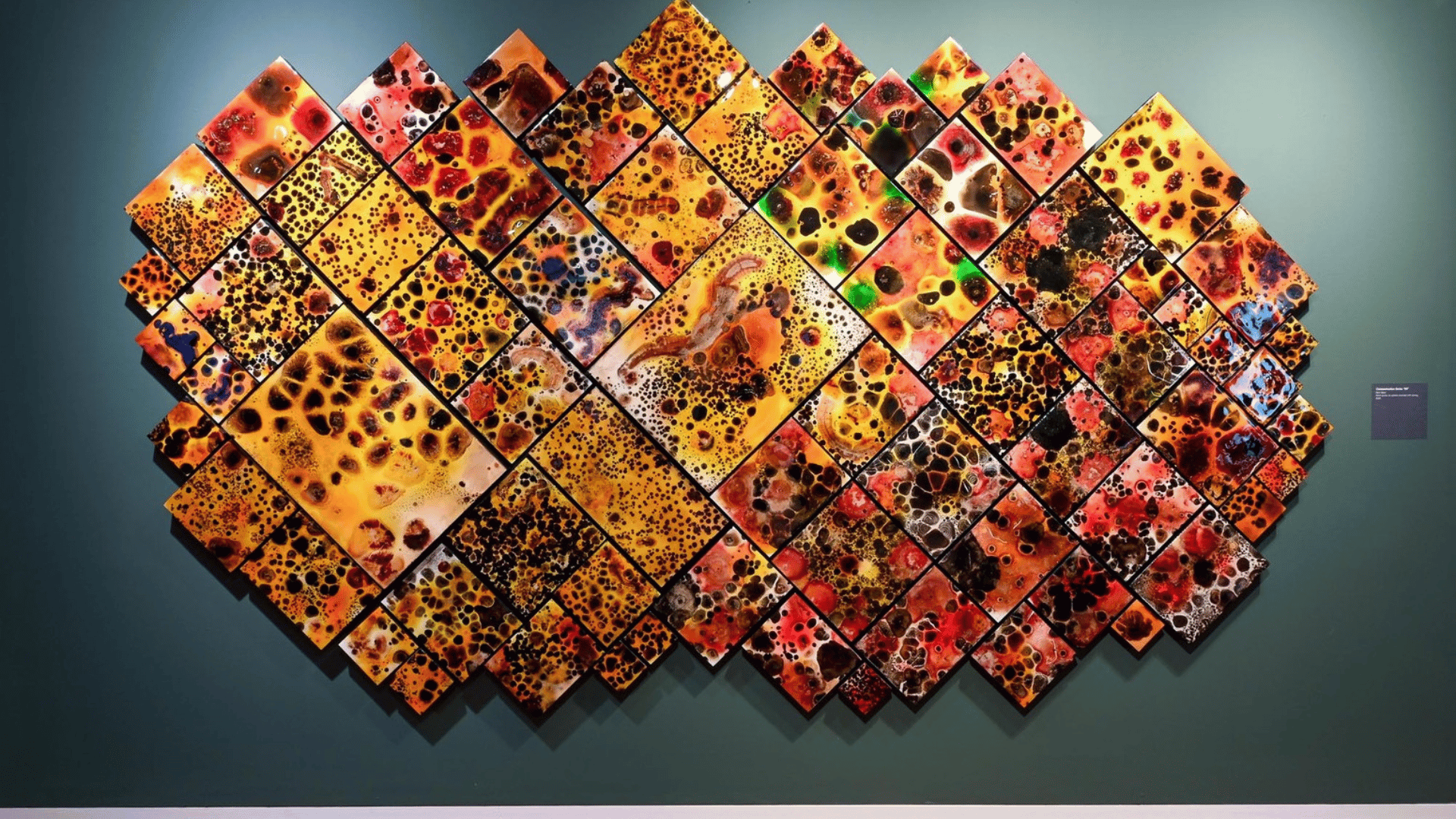

These uninvited microorganisms expand the narrative. New colors and forms emerge from species I didn’t intentionally select, becoming quiet collaborators in the final composition. This unpredictability led to one of my ongoing series, Contamination, where the presence of these “outsider” organisms becomes a conceptual and visual strength of the work. Each piece reflects both my intention and the spontaneous interventions of the natural world, creating a dynamic ecosystem on the picture surface.

TWT: Does nature inspire your art? If so, how?

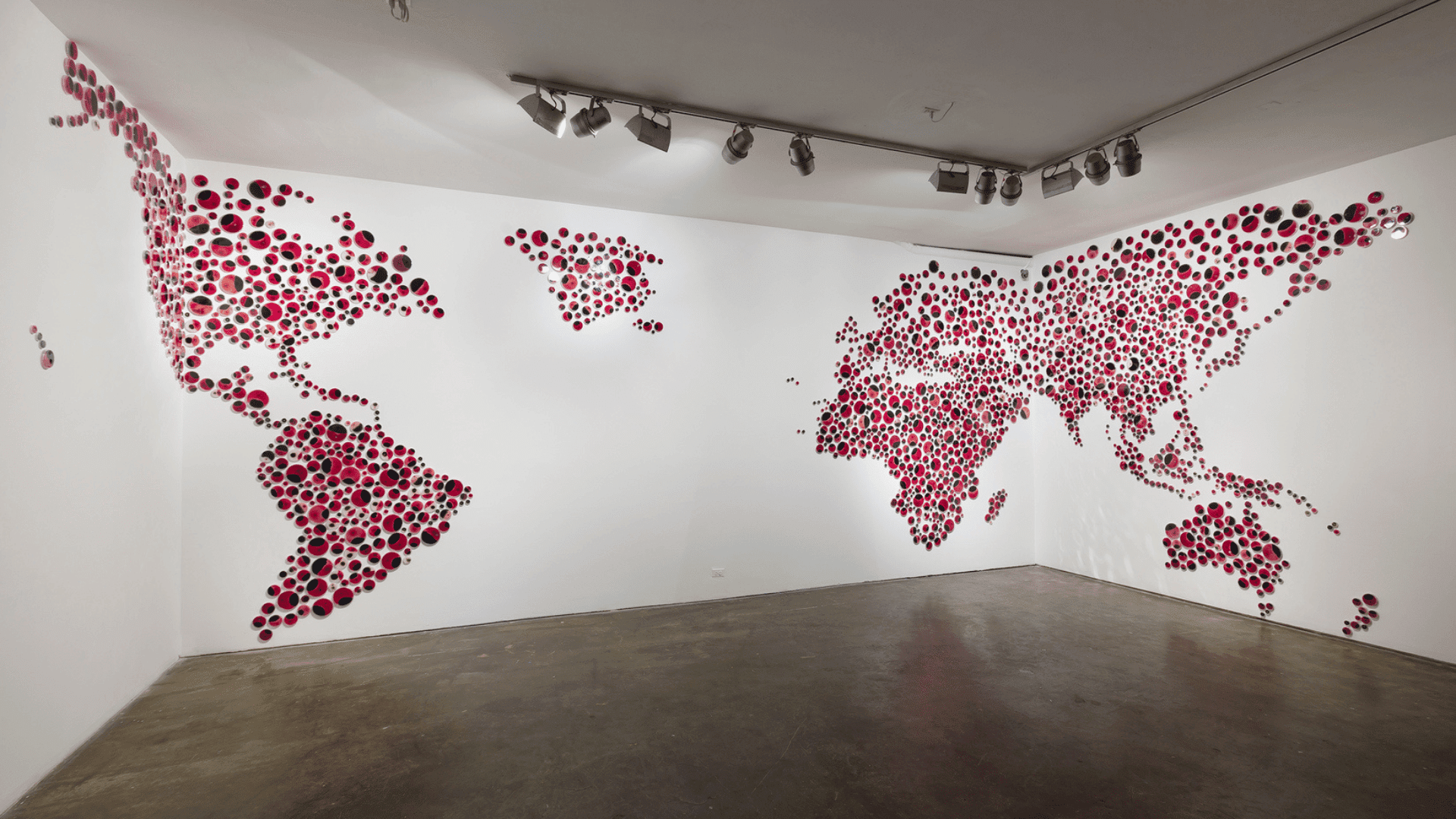

SB: Absolutely. Nature is both my collaborator and my subject. My background in forestry gave me a deep appreciation for ecosystems, cycles, and resilience. I’m inspired not only by the beauty of natural forms, but also by the complexities and harsh realities of ecological systems, competition, decay, and regeneration. My work often mirrors these processes, reminding viewers that the smallest organisms hold immense power in shaping our world.

TWT: Tell us about a few of your favorite pieces you’ve created. Why are they your favorites?

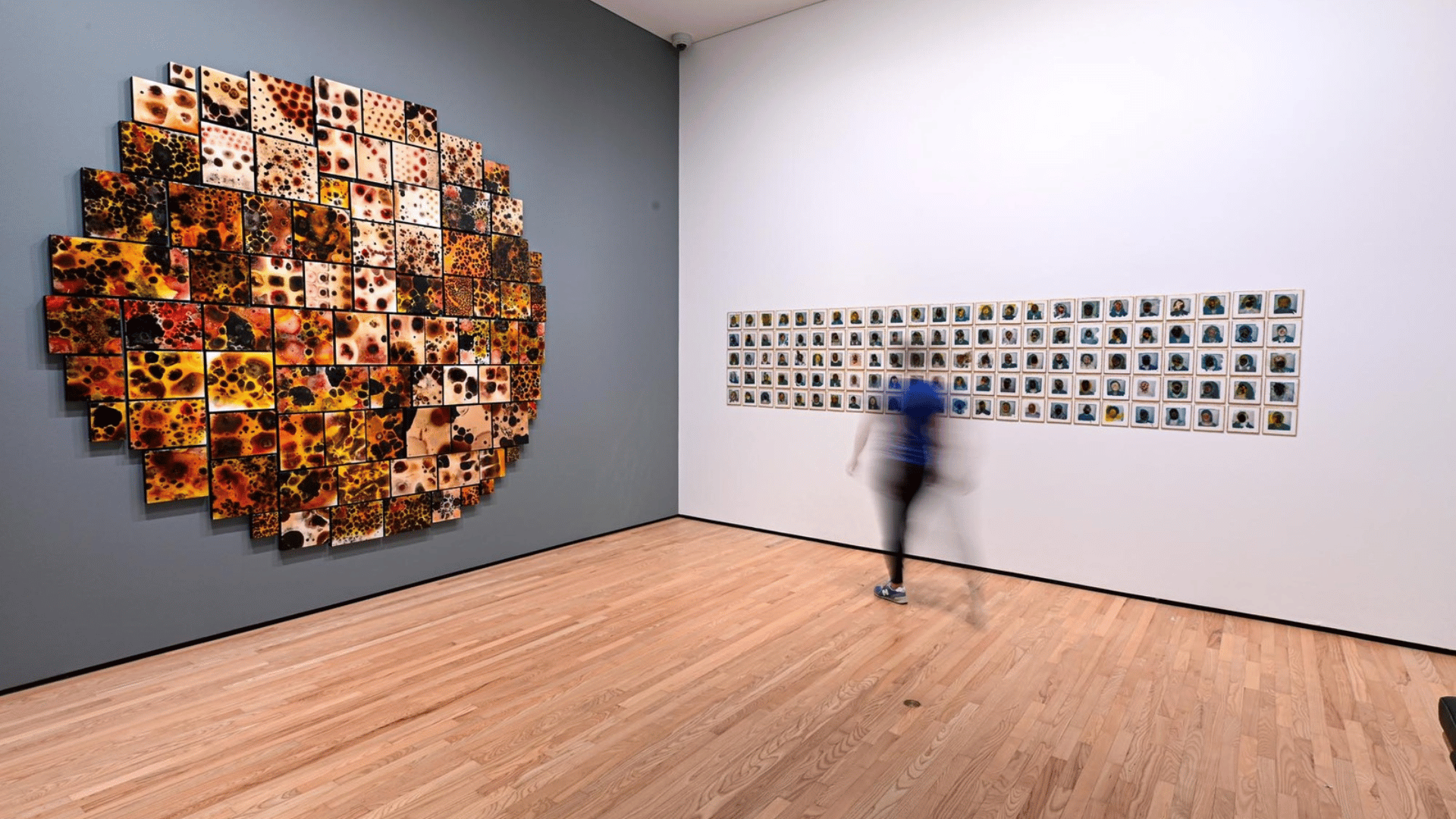

SB: My Contamination series holds a very special place in my career because it was the first time I truly understood how microbial growth could serve as an artistic medium. One of the most meaningful works in this series was created for my exhibition at the Baltimore Museum of Art, where I collected mold spores from Wyman Park, the green space right beside the museum. It became a site-specific work. I took what we normally can’t see in the park and transformed those invisible organisms into a large-scale visual ecosystem. That project connected place, community, and microbial life in a way that still resonates deeply with me. It marked a turning point in my practice, shifting me from trying to control contamination to embracing nature as an active collaborator.

My Faces series is another favorite because it merges portraiture, identity, and microbiology in such an intimate way. Each portrait is literally grown from the subject’s own microbial imprint, becoming a living extension of their identity. It’s a deeply personal series that reveals something about the subject beyond the surface, something that exists in the body’s unseen layers.

A more recent project I am working on is ‘Eroded Landscapes: Microbial Intervention on Polaroid Memory.’ This work combines ecology, photography, and biological decay in a way that feels both poetic and unsettling. By allowing mold spores to gradually consume Polaroid photographs, objects as delicate and unreproducible as ecosystems, I explore environmental memory and ecological loss through a genuine biological process of erasure. The immersive time-lapse projections draw viewers into the microbial takeover, making the slow violence of ecological collapse feel immediate and all-encompassing. Each of these works represents a different moment of growth in my practice. Still, they are all connected by the same thread: using the smallest forms of life to tell much larger stories about identity, ecology, place, and the fragile systems we depend on.

TWT: What brings you the most joy when people see your pieces?

SB: I love witnessing the moment of surprise, the instant when someone realizes that the work is made from living organisms, not just a photograph of a microscopic view. That shift in perception opens a door. People begin asking questions, contemplating their own bodies, their environment, and the invisible worlds around them. When my work sparks curiosity or helps someone feel more connected to nature, that’s the greatest joy.

TWT: How has your work evolved over time? How have you grown as an artist?

SB: In the beginning, my work was very experimental. I was testing how different species behaved, how they interacted, and how far I could push biological materials on an artistic surface. Over time, the conceptual framework has deepened. I’ve become more focused on ecological themes, human identity, and the ethics and responsibilities that come with working with living organisms. My practice has expanded into new mediums as well, integrating photography, installation, sculptural forms, and time-based processes.

During my MFA studies, I knew the medium had incredible potential, but I didn’t yet understand how to integrate biological growth into art materials in a stable, archival, or intentional way. Most of my professors were painters or sculptors, so there was always pressure to create a physical object at the end of the process. But with living organisms, stopping the growth and preserving the surface isn’t simple. It took years of trial and error to figure out how to stabilize the work without losing its integrity. Now I’m able to preserve the growth and maintain the physical imprint of the microorganisms, which has opened the door to more ambitious projects.

A big part of my evolution has also been learning to embrace contamination. At first, I fought against it, using UV lights, bleach, anything I could to keep unwanted species out. But eventually I realized that I wasn’t making scientific samples; I was collaborating with nature. Accepting the unpredictability of contamination made the work richer and more alive.

There are still constant challenges with this medium, and that’s what keeps me energized. I’m always researching new materials to pair with mold spores, plaster, ceramics, Polaroids, and photographic emulsions, and exploring how microorganisms behave on different surfaces. That research-driven curiosity is the science part of me, and it continues to shape how my work grows and evolves.

TWT: What advice would you give to aspiring artists?

SB: Stay curious and follow the things that genuinely fascinate you, even if they seem unconventional. Your uniqueness is your greatest strength. Don’t be afraid of experimentation, failure, or slow progress; those moments often lead to the most meaningful breakthroughs.

I also encourage young artists to bring their whole lives into their work. Don’t limit yourself to a single identity or discipline. My own practice grew when I allowed my background in microbiology, photography, and mixed media to coexist. Interdisciplinary thinking opens new doors, and the more you integrate your personal history, culture, and interests, the more authentic and expansive your work becomes.

As a teacher, I always push my students to make their work personal and to embrace what sets them apart. We brainstorm constantly, searching for new approaches and unexpected solutions. That process of exploration, of trying, failing, and trying again, is where an artist’s voice truly begins to develop.

Above all, build a practice that feels true to you. Art grows naturally when you trust yourself, stay open, and let all parts of your life shape your creativity.

For more information about Selin Balci and her projects, follow her on Instagram and on selinbalci.com.