Treating brain cancer is incredibly difficult because no two tumors act exactly the same. Some respond to drugs, while others resist them. Some slow down if the patient changes their diet, while others keep growing no matter what the patient eats.

Figuring out which treatment will work usually involves a lot of trial and error. However, researchers at the University of Michigan have found a way to test treatments without experimenting on the patient first. They developed a computer-based “digital twin” of a patient’s brain tumor.

This new approach uses machine learning to map out exactly how a tumor eats and grows in real-time.

How the Digital Twin Works

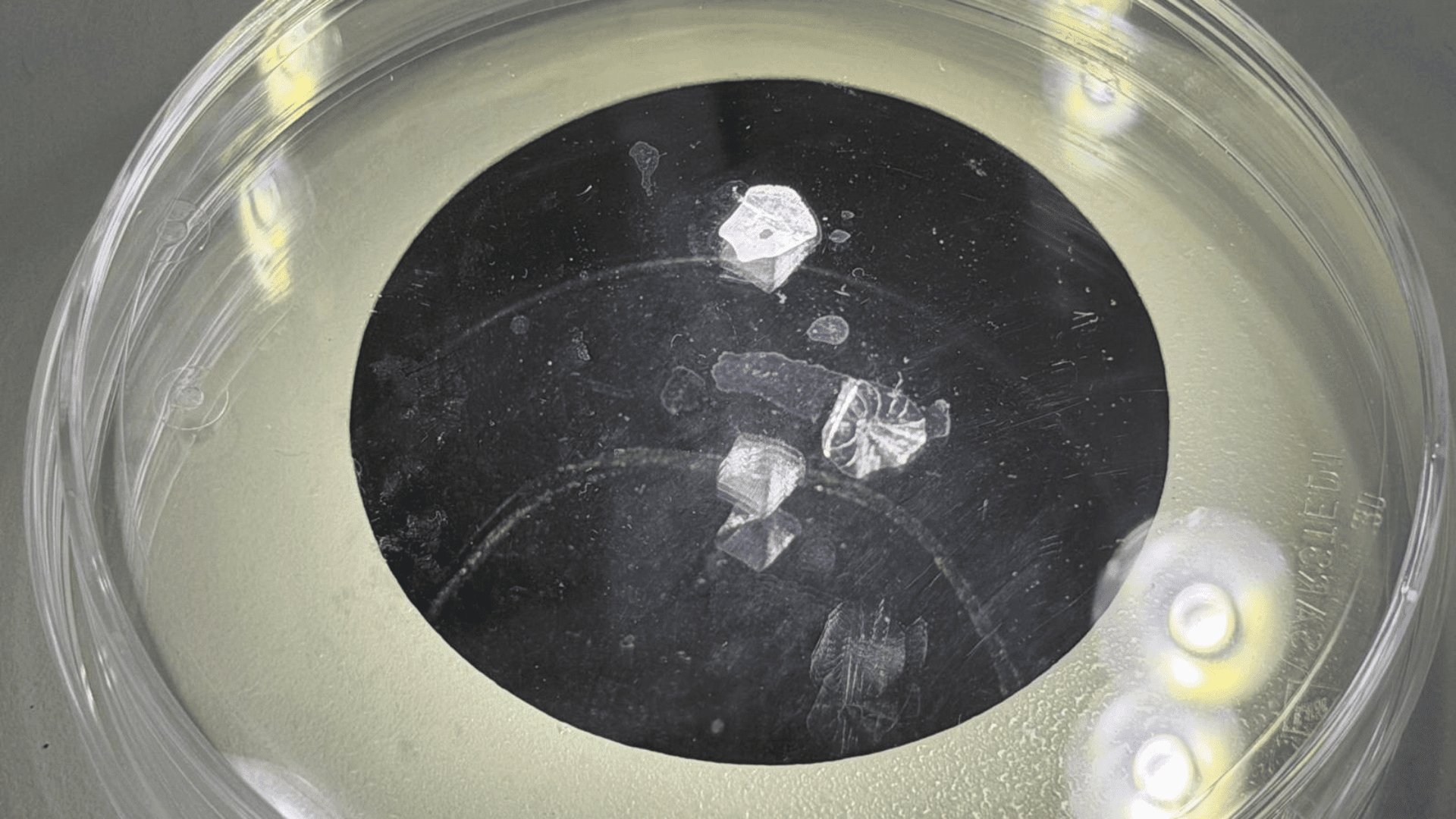

The team, funded primarily by the National Institutes of Health, created a deep learning model. They feed it data from a patient’s blood, the tumor’s genetics, and tissue samples. The computer then creates a simulation, a digital twin, that predicts how that specific tumor will react to different situations.

It essentially calculates the speed at which cancer cells process nutrients.

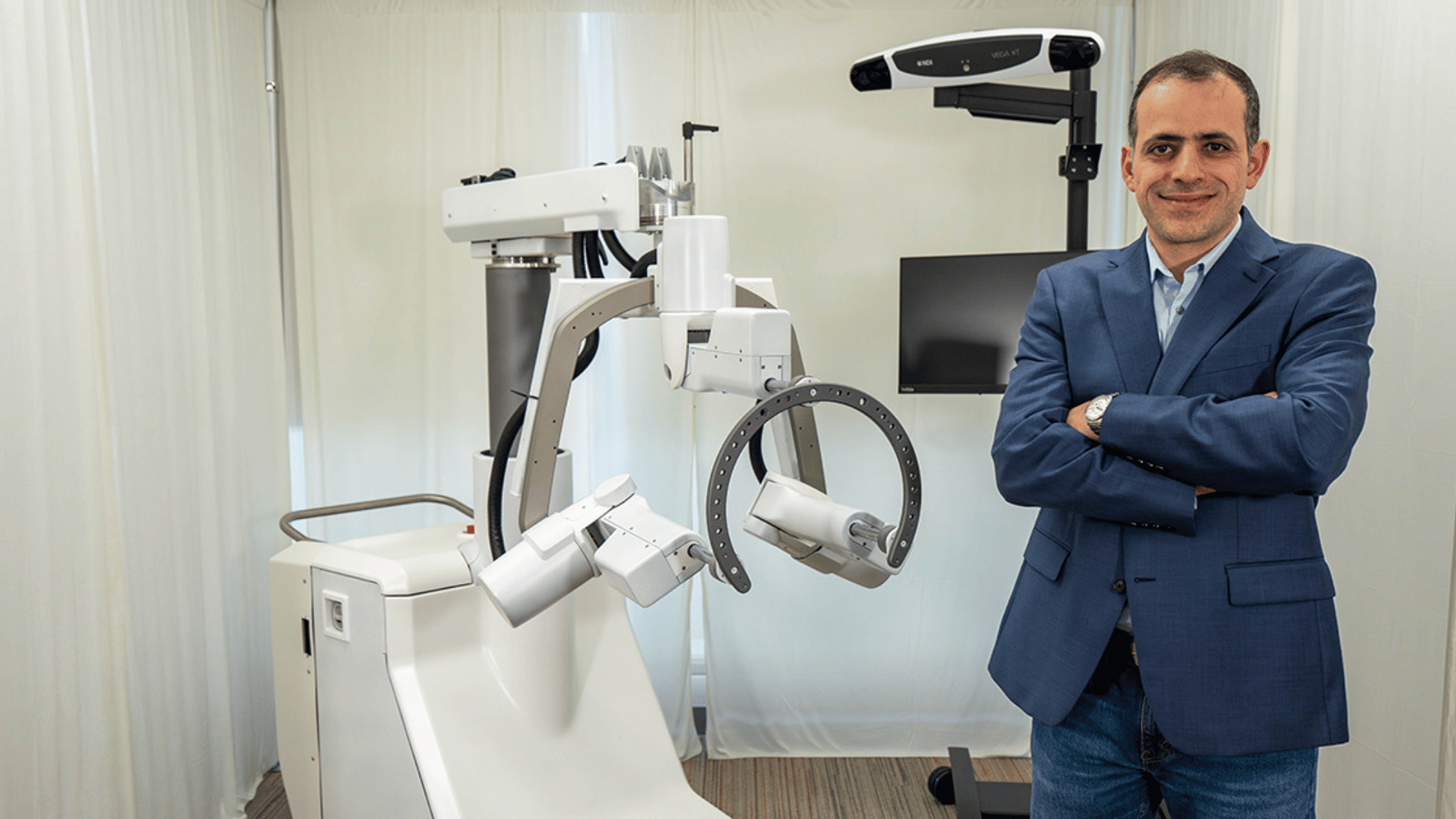

“Typically, metabolic measurements during surgeries to remove tumors can’t provide a clear picture of tumor metabolism—surgeons can’t observe how metabolism varies with time, and labs are limited to studying tissues after surgery,” said Deepak Nagrath, a U-M professor of biomedical engineering. “By integrating limited patient data into a model based on fundamental biology, chemistry, and physics, we overcame these obstacles.”

Baharan Meghdadi, a doctoral student and co-first author of the study, said, “This is the first time a machine learning and AI-based approach has been used to measure metabolic flux directly in patient tumors.”

Advertisement

Why This Matters for Patients

According to the research team, when they tested the model against human patient data and ran experiments on mice, the results were promising.

For example, scientists know that some tumors stop growing if you cut out certain proteins from a diet. However, other tumors make those proteins themselves. Researchers say the digital twin correctly identified which mice would actually benefit from a diet change.

Additionally, it predicted drug resistance. When testing a drug designed to stop cancer cells from building DNA, the model spotted which tumors would survive by using a “salvage pathway” to get nutrients from their neighbors.

“This amazing tool could help doctors avoid prescribing treatments that a specific tumor is already equipped to resist, and is a way for us to move towards more targeted and personalized treatments for our patients,” said Wajd N. Al-Holou, a neurosurgeon involved in the study.

The goal is to eventually use this for more than just brain cancer.

“This work moves us closer to truly personalized cancer care—not just for brain cancer, but eventually for a variety of tumors. By simulating different therapies virtually, we hope to spare patients from unnecessary treatments and focus on those likely to help,” said Costas Lyssiotis, a professor of oncology.

The team has applied for a patent and is currently looking for partners to get this technology out of the lab and into hospitals.