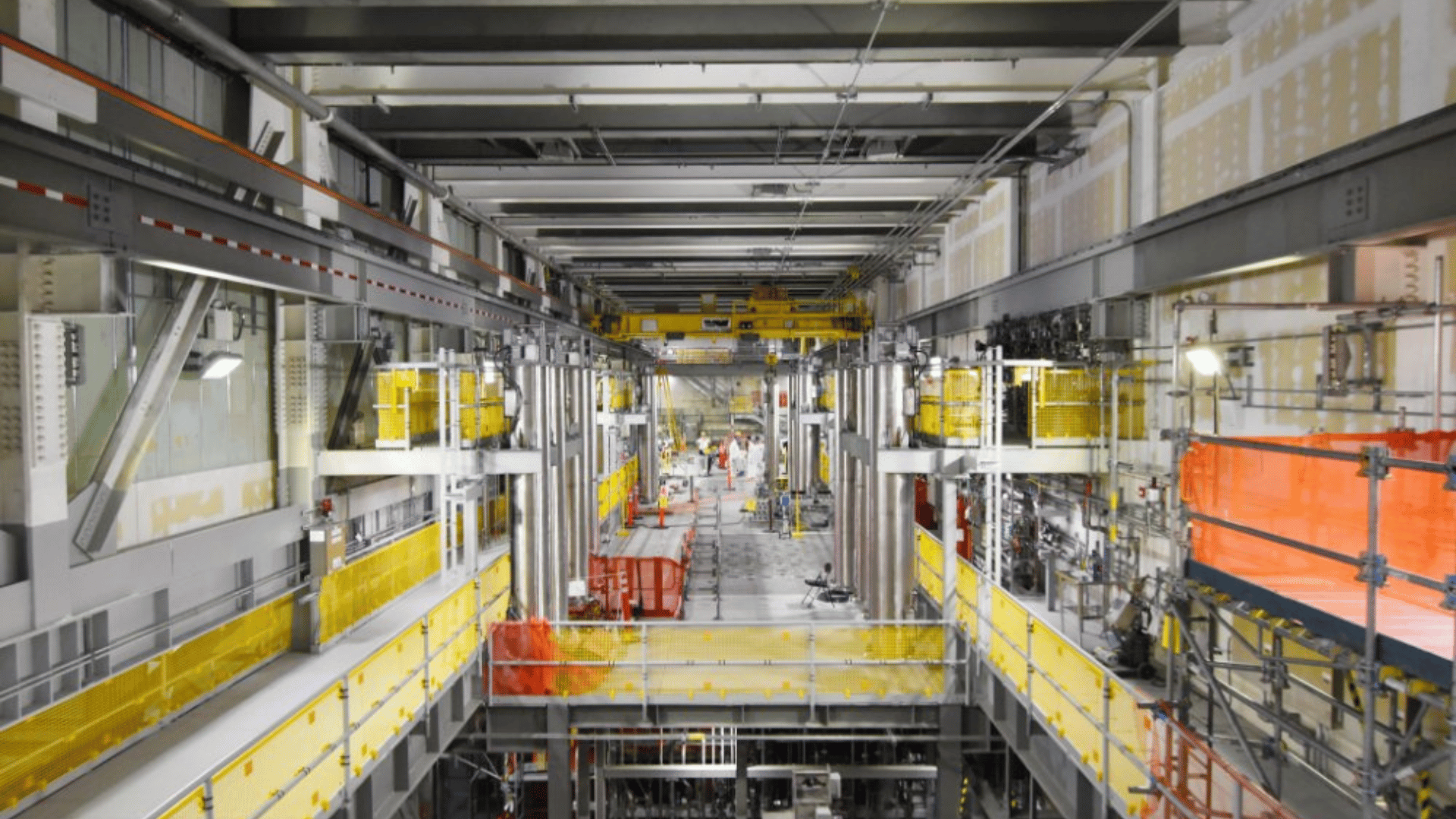

Cleaning up the Hanford Site in Washington is a massive job. It involves dealing with decades of nuclear contamination, and for a long time, it felt like a slow grind. But recently, the project hit some major milestones that are actually pretty cool from a technology standpoint.

The big news is that for the first time, engineers are successfully turning radioactive waste into a solid, stable glass form. It’s a process called “vitrification,” and it is finally happening after years of planning.

The Science of Nuclear Cleanup

Here is how it works. The site holds millions of gallons of radioactive waste in tanks. To make it safe, they are using a program called Direct-Feed Low-Activity Waste.

The waste travels from the storage tanks to a treatment facility. Once there, it gets mixed with glass-forming materials and fed into massive 300-ton melters. These things are beasts, about 20 feet by 30 feet, and they heat the mixture to 2,100 degrees Fahrenheit.

After the mix melts, it is poured into stainless steel containers. Each container holds 6.6 tons of the new glass product. When the facility is running at full speed, they expect to produce up to five of these containers every single day. This is a big deal because glass is solid and stable, unlike the liquid waste they started with.

The Cost of Progress

While the tech is impressive, running these facilities is expensive. The Washington State Department of Ecology estimates it needs a budget of $6.15 billion for 2026 to keep everything on schedule. They received over $3.2 billion this year, which is helpful, but still short of the full amount needed to meet all legal cleanup milestones.

If the funding drops, the timeline drags out, and the total cost goes up. But the progress made so far is undeniable.

“Over the last year, we’ve made huge progress at Hanford. Many of these accomplishments have been in the works for decades. We need to keep funding at a level where we can accelerate the pace of cleanup and reduce the risk of a catastrophic infrastructure collapse or contamination release,” Ecology’s Casey Sixkiller explained. “Now is the time for the federal government to double-down and not back away from its legal and moral obligations to the people of Washington state.”

There is still plenty of work ahead, including a new plan to clean up 56 million gallons of tank waste. But seeing liquid nuclear waste turn into harmless-looking glass blocks is a sign that things are moving in the right direction.