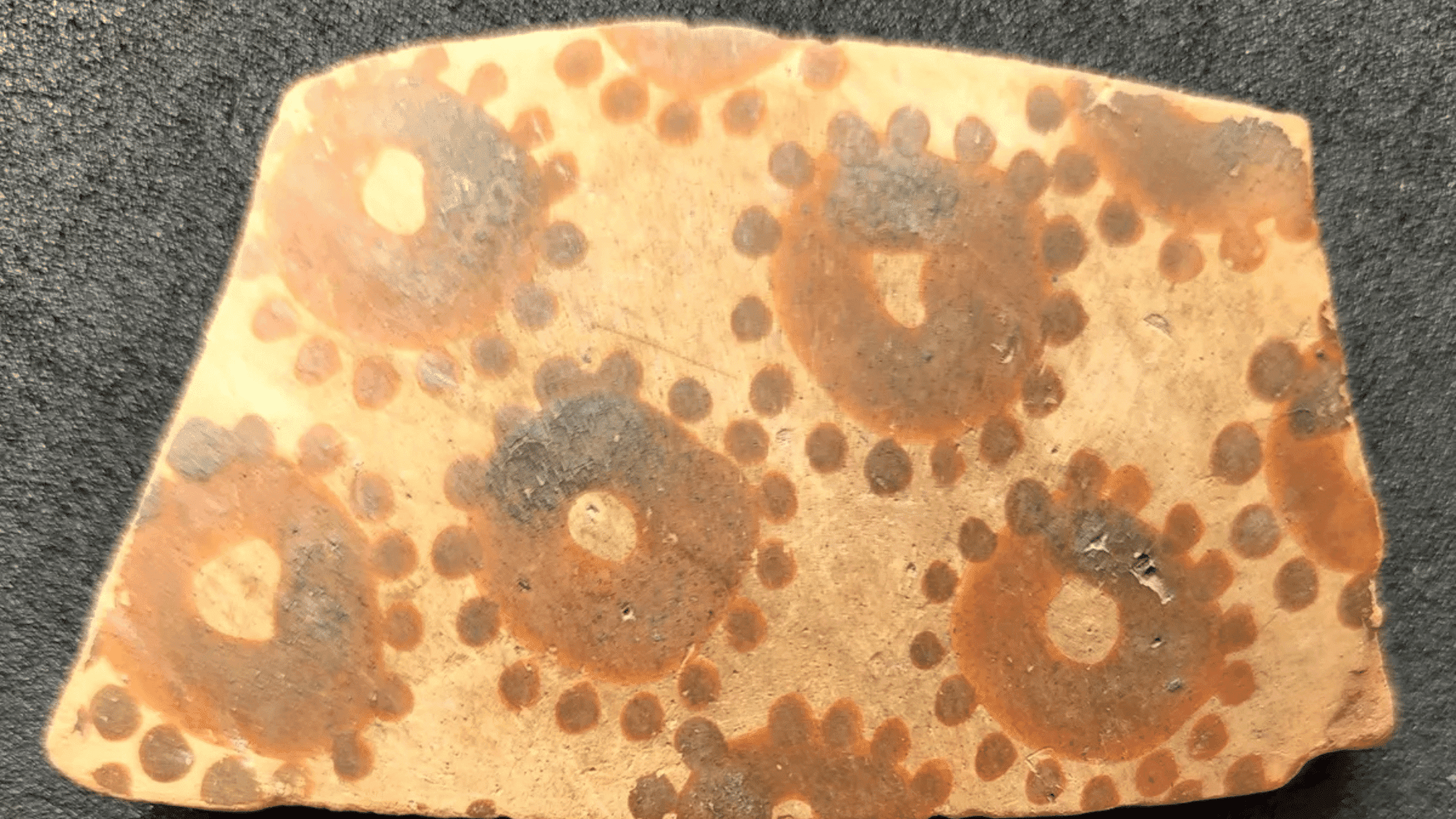

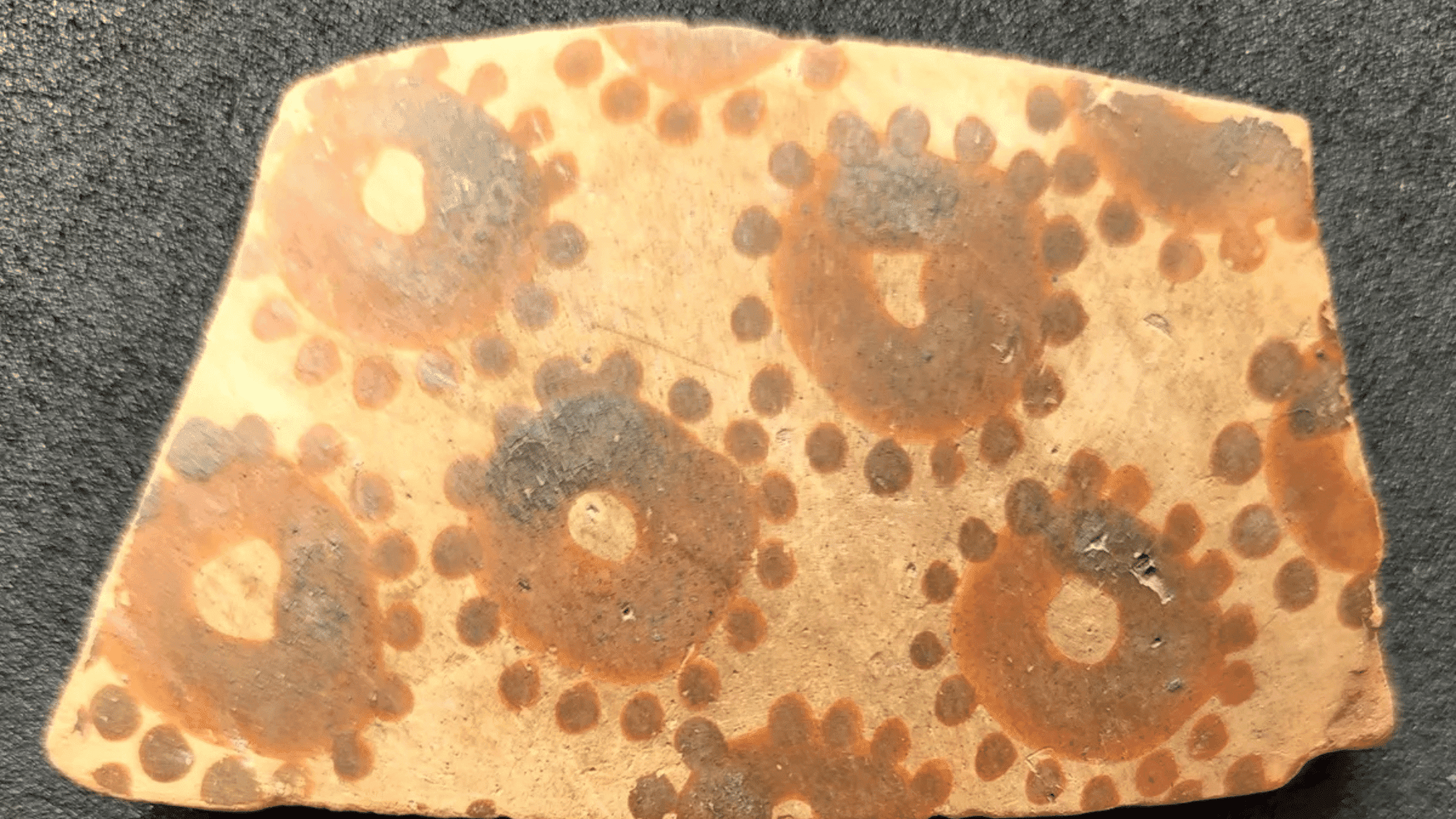

Researchers recently discovered that ancient pots decorated with a floral pattern and potentially containing the origins of mathematical thinking date back further than previously thought.

World’s Oldest Botanical Art

“The earliest systematic depictions of vegetal motifs in prehistoric art appear on painted pottery vessels of the Halafian culture of northern Mesopotamia, c. 6200–5500 BC,” begins a recent paper from researchers at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Institute of Archaeology.

“The depictions of flower petals in the geometric sequence of the numbers 4, 8, 16, and 32, as well as 64 flowers in another type of arrangement, point to arithmetical knowledge.”

This assertion requires us to rethink how different cognitive abilities have developed. For example, rather than developing alongside written language, this would suggest that it’s predated by mathematical thinking by a couple of thousand years.

According to Sarah Krulwich, a Master’s student in the Institute and coauthor of the study, the patterns “show that mathematical thinking began long before writing.”

Advertisement

“People visualized divisions, sequences, and balance through their art,” she said.

Krulwich, alongside archaeology professor Yosef Garfinkel, found nearly 400 examples of botanically decorated pottery fragments uncovered from northern Mesopotamian sites. In most of them, the number of petals is specifically a power of two: 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64.

It’s a discovery that “clearly reflects sophisticated knowledge in the field of symmetry and in the ability to divide the circle into symmetrical units,” the paper points out. “These numbers are not accidental.”

“The study suggests that mathematical cognition developed well before writing, embedded in craft traditions such as pottery painting and seal engraving,” Laurent Davin, an archaeologist at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem who was not involved in the study, told New Atlas. “It shows that complex abstract thinking was already present in Neolithic communities.”

Since the plants shown weren’t crops or edible plants, researchers believe they were drawn for their “positive effect on human emotions”, as opposed to something instructive or practical.

“These vessels represent the first moment in history when people chose to portray the botanical world as a subject worthy of artistic attention,” Krulwich and Garfinkel said. “It reflects a cognitive shift tied to village life and a growing awareness of symmetry and aesthetics.”

The paper is published in the Journal of World Prehistory.