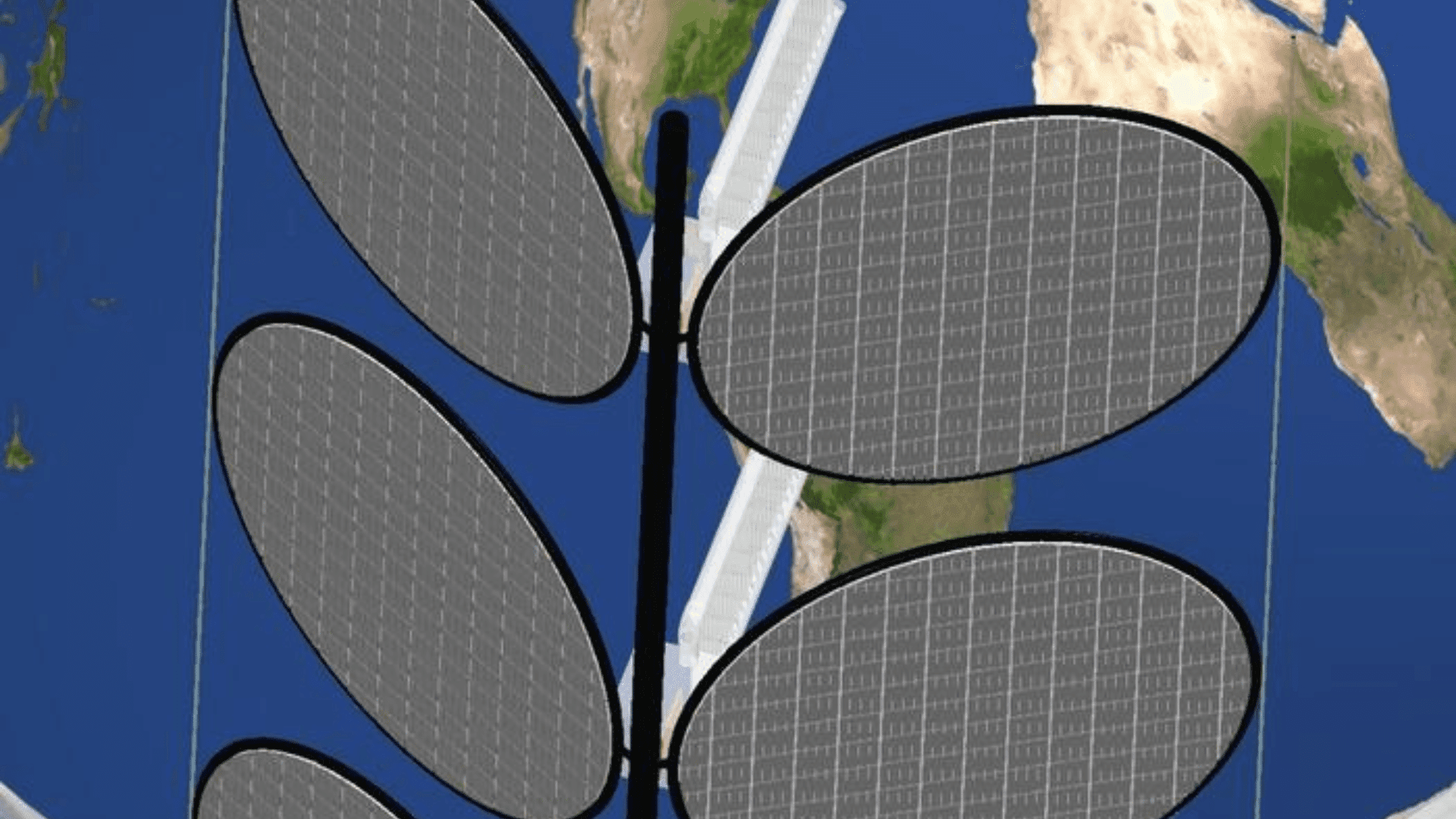

As AI tools like ChatGPT become part of daily life, the energy and water needed to run the massive data centers behind them are becoming a problem. To solve this, engineers at the University of Pennsylvania are looking to the sky. They’ve designed a way to put AI data centers into orbit, using a design that looks less like a satellite and more like a leafy plant.

The concept uses “tethers,” long, flexible cables that have been studied for decades. These cables naturally pull themselves straight in space because of how gravity and orbital motion work. By attaching computer “stems” and solar-panel “leaves” to these cables, the team believes they can build a system that stays pointed at the sun without using heavy motors or constant fuel.

Powering AI From Orbit

Most current ideas for space data centers involve giant, rigid structures that would be hard to build, or millions of tiny satellites that are hard to coordinate. Igor Bargatin, an Associate Professor at Penn, said, “If you rely on constellations of individual satellites flying independently, you would need millions of them to make a real difference.”

Instead, the Penn design is modular. You can keep adding computing nodes to a cable. These nodes use the pressure of sunlight to stay balanced.

“This is the first design that prioritizes passive orientation at this scale,” said Bargatin. “Because the design relies on tethers, an existing, well-studied technology, we can realistically think about scaling orbital data centers to the size needed to meaningfully reduce the energy and water demands of data centers on Earth.”

Built to Last

Space is a complicated and crowded place, filled with tiny bits of debris and dust called micrometeoroids. Since these data centers would be kilometers long, they are bound to get hit. However, the team found that the tether design is naturally resilient. If a piece of debris hits the structure, it just wobbles for a bit before settling back down.

“It’s a bit like a wind chime. If you disturb the structure, eventually the motion dies down naturally,” said Jordan Raney, an Associate Professor and co-author of the study. “We had to understand how long that process would take, to be sure that the data center would be stable even when hit by multiple objects.”

The goal isn’t to train new AI models in space, but to handle the “queries,” or the millions of questions users ask every day. By moving that workload to orbit, we could take a lot of pressure off our power grids here on the ground.