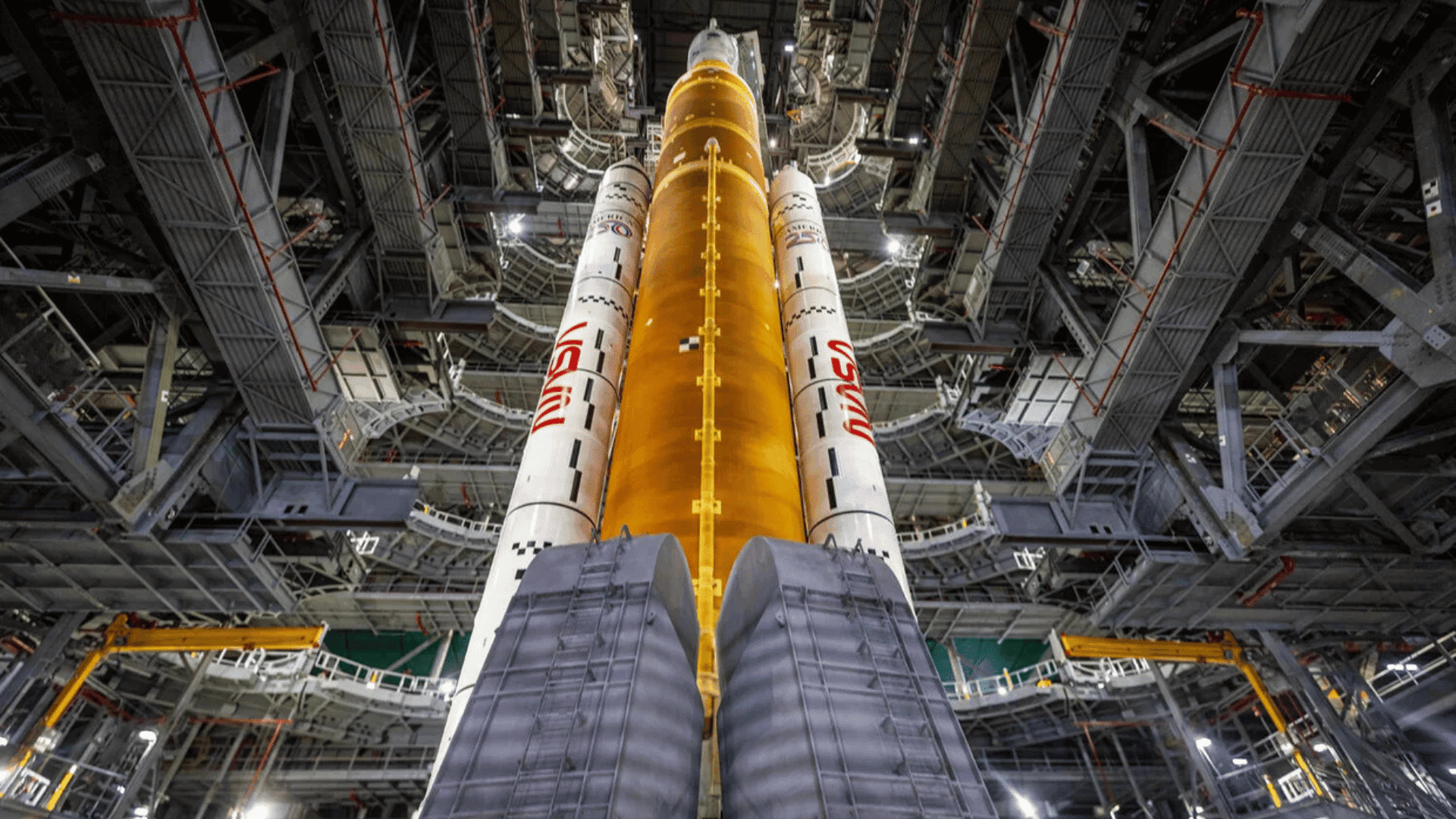

Earth’s orbit is getting overcrowded, whether it’s with satellites or space debris. Over the last few years, the number of spent spacecraft and random debris falling back to Earth has grown. These uncontrolled reentries are happening more often, and they pose risks to people and the environment. Additionally, some of these objects can even carry toxic, flammable, or radioactive materials.

However, the issue is that redirecting exactly where a dying satellite will crash is incredibly difficult. Ground-based radar and optical systems are great, but they struggle to track debris once it starts disintegrating in the atmosphere.

If you can’t track it, you can’t warn people or plan a response. But researchers Benjamin Fernando and Constantinos Charalambous have found a way to track this debris in near real-time, and they are doing it by listening to the ground.

Tracking Space Debris With Sonic Booms

The researchers demonstrated a method using publicly available data from seismic sensors, the same tools used to study earthquakes, to detect the shockwaves, or sonic booms, caused by reentering debris.

Advertisement

To prove their theory, they looked at the April 2024 reentry of the Shenzhou-15 orbital module. This was a heavy piece of equipment left in a decaying orbit that passed over major population centers on six continents. The official tracking prediction said Shenzhou-15 would reenter over the northern Atlantic Ocean. It missed that mark by about 5,300 miles (8,600 kilometers).

However, by using seismic sensors across Southern California and Nevada, the researchers analyzed the sonic booms as the module came down. They inserted the arrival times of the shockwaves to figure out the spacecraft’s ground track, speed, and altitude. The data also showed that the module did not explode all at once but likely fragmented progressively into smaller pieces. This matched up perfectly with video footage and eyewitness reports.

Filling a Gap

This method fills a big gap in our current technology. Being able to track uncontrolled space debris as it reenters orbit helps authorities pinpoint impact locations and figure out where hazardous particles might spread. It is crucial for recovery teams and contamination mitigation.

“Further research is needed to reduce the time between an object’s (re)entry in the atmosphere and the trajectory determination,” Chris Carr, who wrote a perspective on the study, said. “Nonetheless, the method used by Fernando and Charalambous unlocks the rapid identification of debris fall-out zones, which is key information as Earth’s orbit is anticipated to become increasingly crowded with satellites, leading to a greater influx of space debris.”