Most scientists hate it when their experiments fail. But researchers at the University of Chicago actually went looking for failure. For three years, Asst. Prof. Chibueze Amanchukwu and his team read through old studies about batteries breaking down.

They weren’t trying to fix the batteries. They realized the same chemical reaction that ruins a battery might be the secret to destroying “forever chemicals,” or PFAS.

“If somebody complains, ‘Oh, this compound degrades in this manner and leads to a poorly cycling battery,’ we get excited about that,” Amanchukwu said. “Because we can flip it around for PFAS degradation.”

Battling Forever Chemicals

PFAS are everywhere, in raincoats, non-stick pans, and firefighting foam, to name a few. They are called “forever chemicals” because the carbon-fluorine bonds holding them together are incredibly strong. As a result, they don’t simply go away.

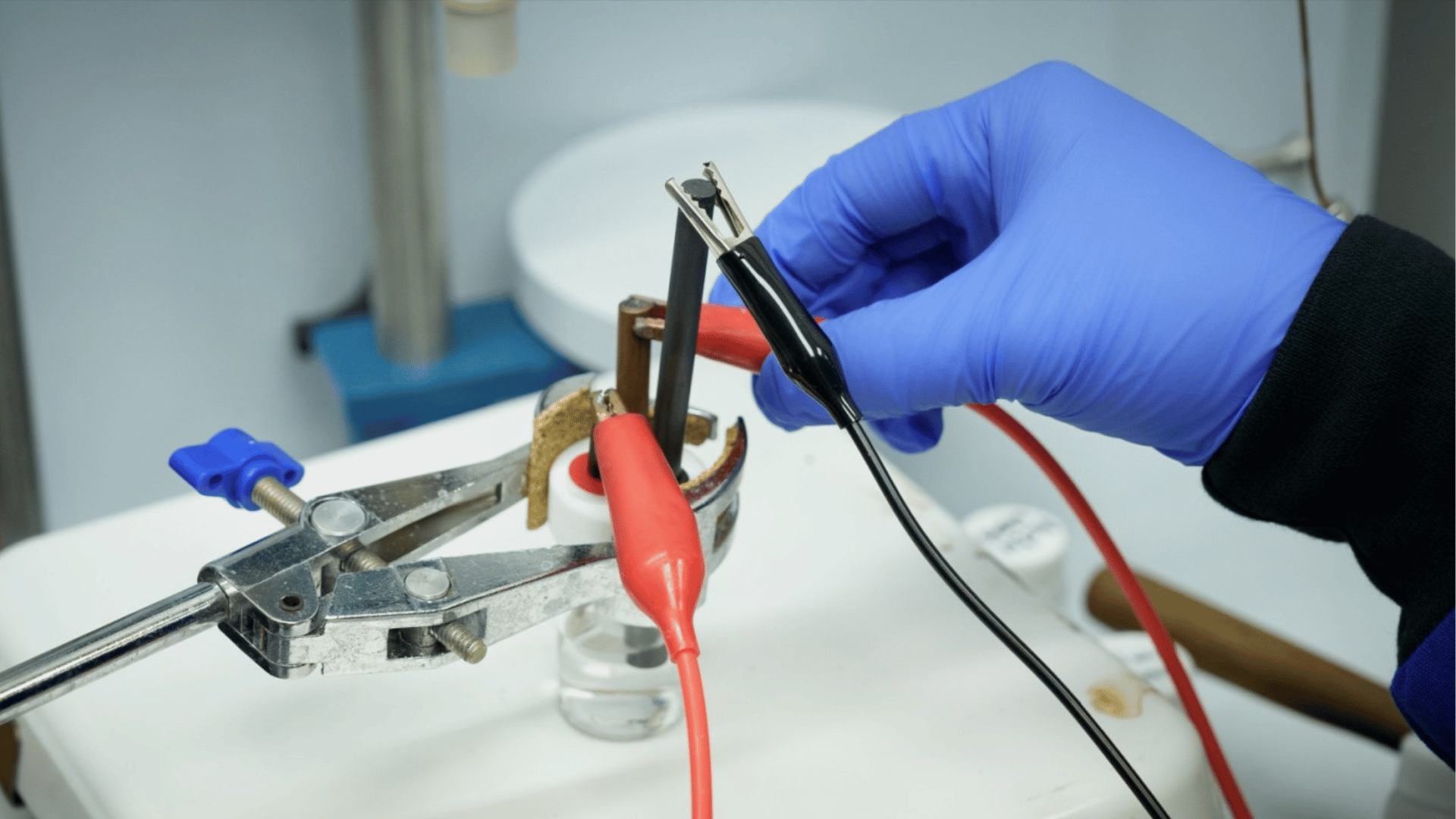

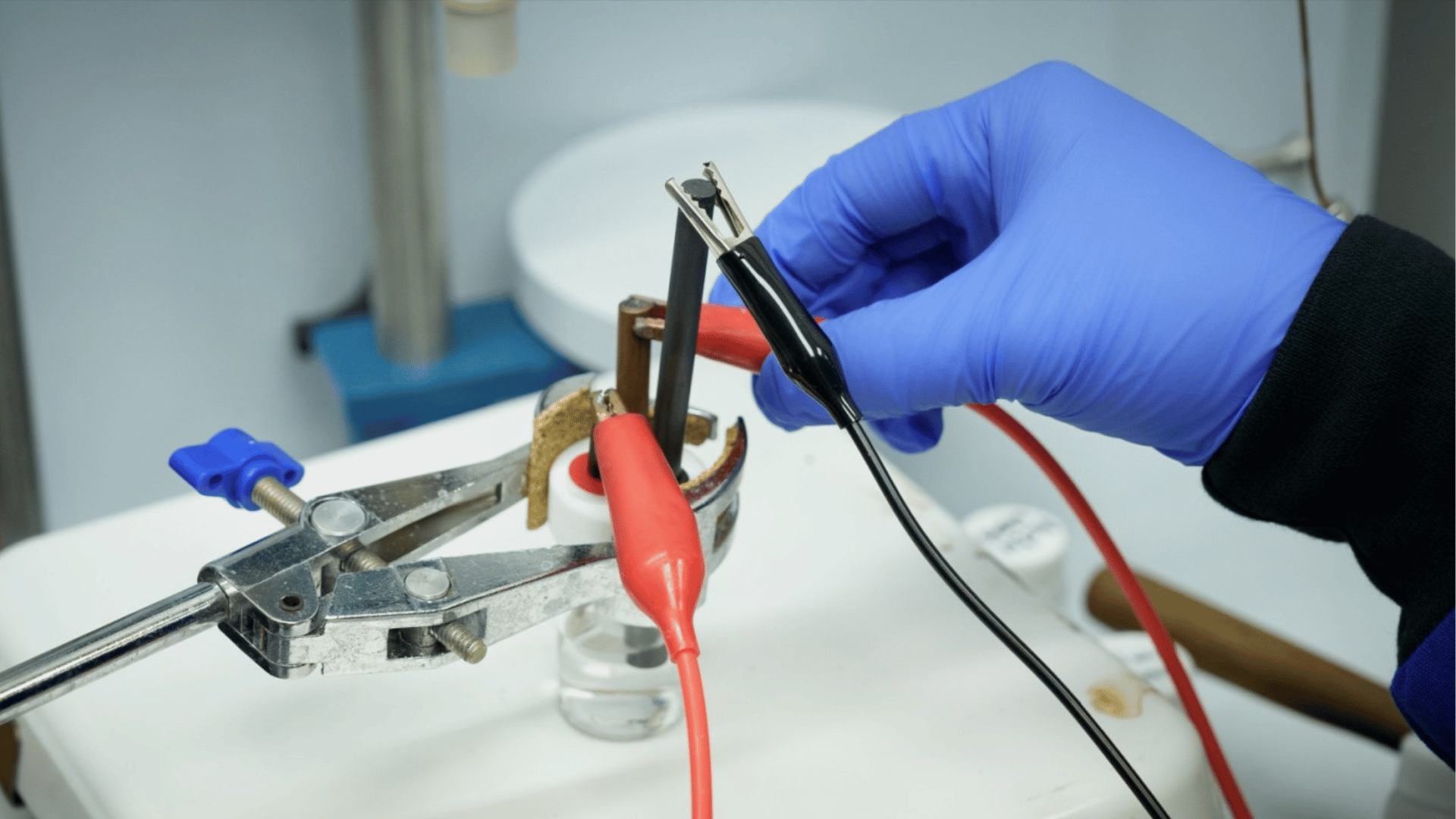

Working with researchers from Northwestern University, the team found a way to use those battery-killing conditions to break those tough bonds. Their results, published in Nature Chemistry, show they can shatter the stubborn PFAS molecules almost completely.

“We achieve about 94% defluorination and 95% degradation,” said Bidushi Sarkar, a postdoctoral researcher who led the study. That means we break nearly all the carbon–fluorine bonds in PFAS.”

Advertisement

This is important because other methods often just chop the chemicals into smaller, still-harmful pieces. This method turns them into harmless minerals that can actually be reused.

Turning Questions Into Answers

The idea for this project actually came from a tough question. Amanchukwu usually works on making batteries better, but people kept worrying about the chemicals inside them.

“No exaggeration, when I would give talks, I guarantee you a question I would get at the end would be ‘Professor, why are you making more forever chemicals?'” Amanchukwu said.

Instead of getting defensive, the team got creative. They realized that if PFAS-based electrolytes fall apart in batteries, they could control that process to clean up pollution.

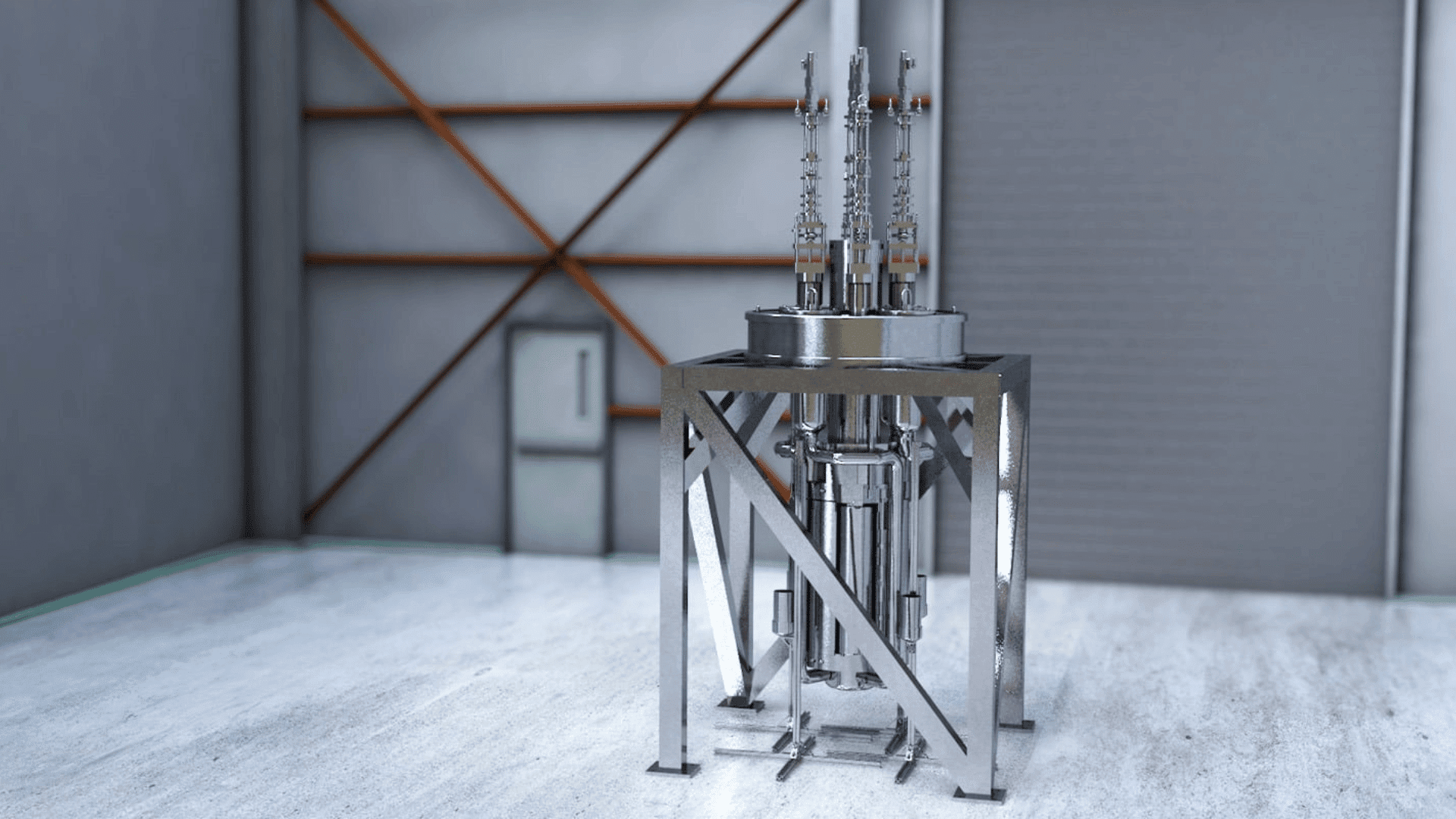

And because this uses electrochemistry, essentially electricity interacting with chemicals, it doesn’t require a massive, hot factory to work. It can be done almost anywhere.

“The reason people love electrochemistry is that it is quite modular,” Amanchukwu said. “I can have a solar panel with batteries, and I can have an electrochemical reactor on site that is small enough to deal with any local waste streams.”