Scientists at RMIT have found a way to turn industrial smoke into the basic ingredients for jet fuel. They made a complicated chemical process simpler so it can work in factories.

Usually, capturing carbon and turning it into something useful are two separate and costly steps. The RMIT team combined these steps. Their system takes carbon dioxide directly from factory exhaust and turns it into basic chemicals. These chemicals can then be used to make low-emissions jet fuel or other products that normally come from fossil fuels.

Making It Practical

The main advantage is not just that this method works, but that it is efficient. Most current methods need a lot of energy and very pure carbon dioxide, which is hard to find in real factories. This new system is more flexible.

Professor Tianyi Ma, from RMIT’s School of Science, explained that older methods just weren’t cutting it. “Current approaches had often been inefficient and energy‑intensive,” Ma said. “By bringing the steps of conversion together, we have been able to simplify the process and reduce unnecessary energy losses.”

Dr. Peng Li, the study’s lead author, noted that the focus was on making something that works in the real world. “Our approach has reduced the number of processing steps and lowered energy demand compared with conventional systems,” Li said. “The RMIT system operates without the need for highly purified carbon dioxide, which is important in real industrial environments.”

The Road to Aviation

Making aviation more sustainable is difficult. Batteries are too heavy for long flights, and there is not enough sustainable fuel available. This technology could help by connecting directly to existing factories.

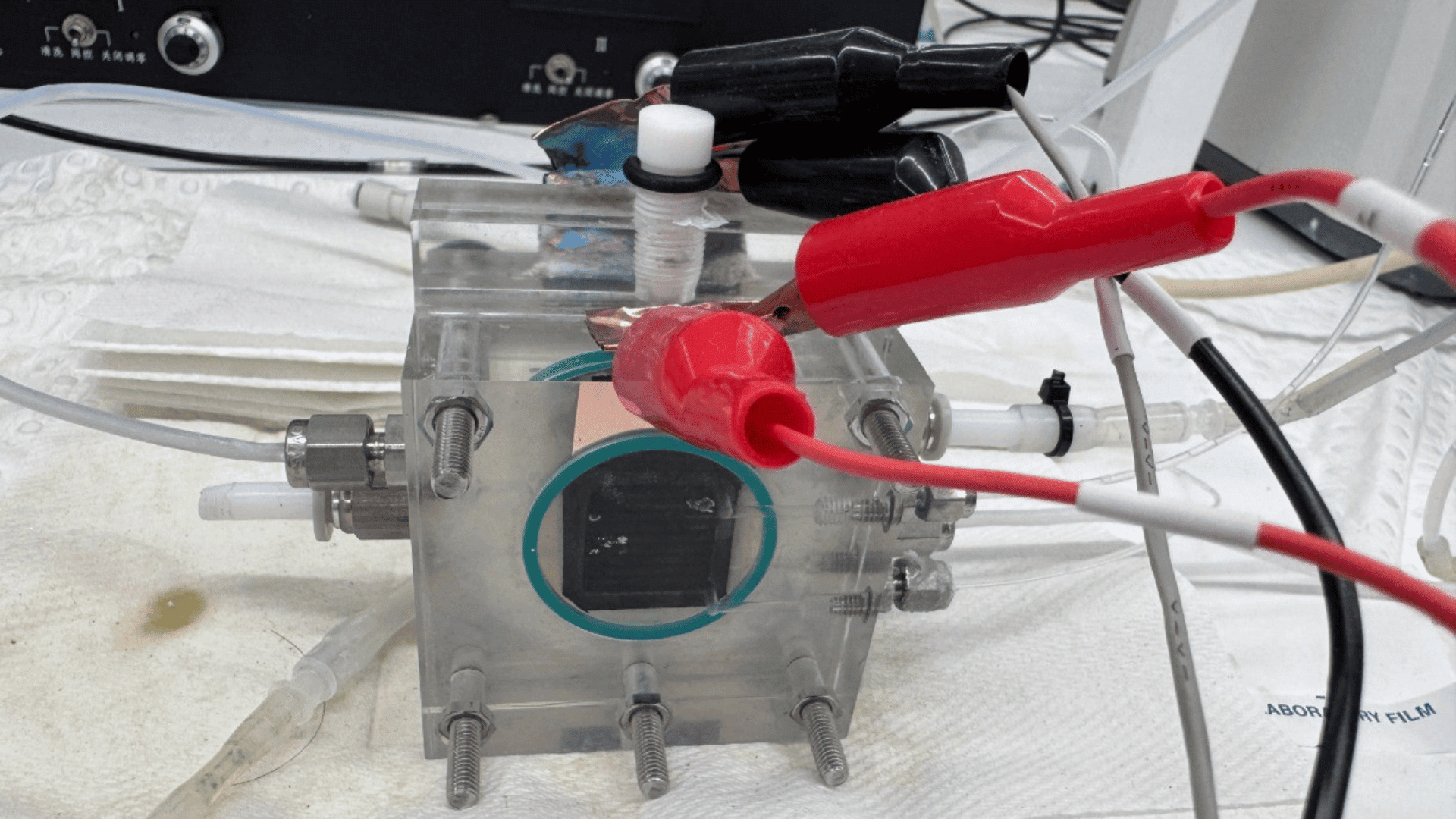

The team is not just working in the lab. They have already built a small 3-kilowatt prototype and are now developing a 20-kilowatt pilot system. They are partnering with energy and bioenergy companies to make sure the technology fits into existing infrastructure.

“Scaling up has to happen hand in hand with industry,” Ma said. “That is the only way to understand what would work in practice and what still needs improvement.”

The aim is to have a system ready for commercial use in about six years. While it will not solve every climate problem right away, it is a useful tool for industries working to reduce their emissions.

Ma said, “This is not a silver bullet. It is about developing practical tools that could help industries and governments reduce emissions while making use of existing systems during the transition to cleaner fuels.”