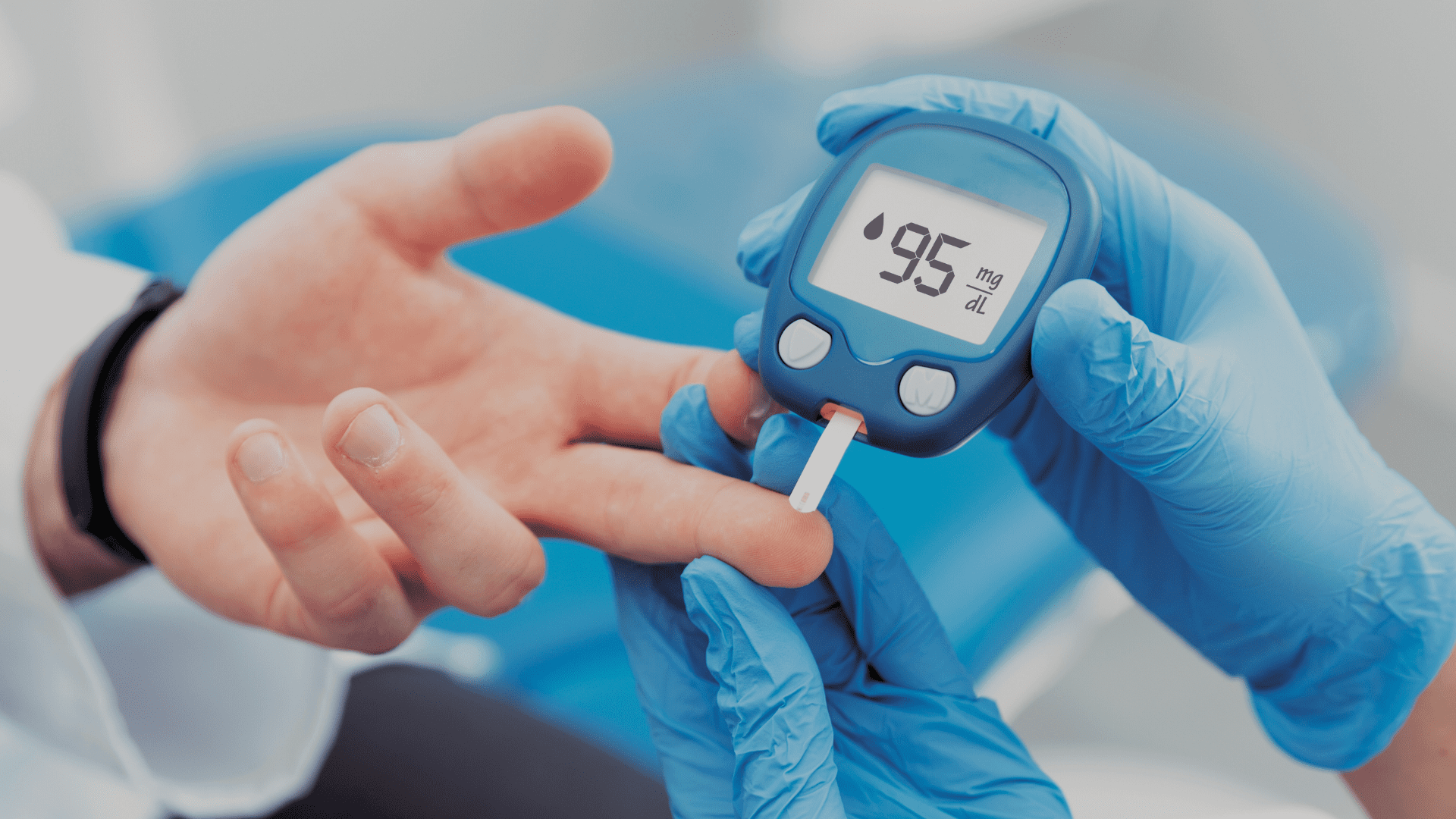

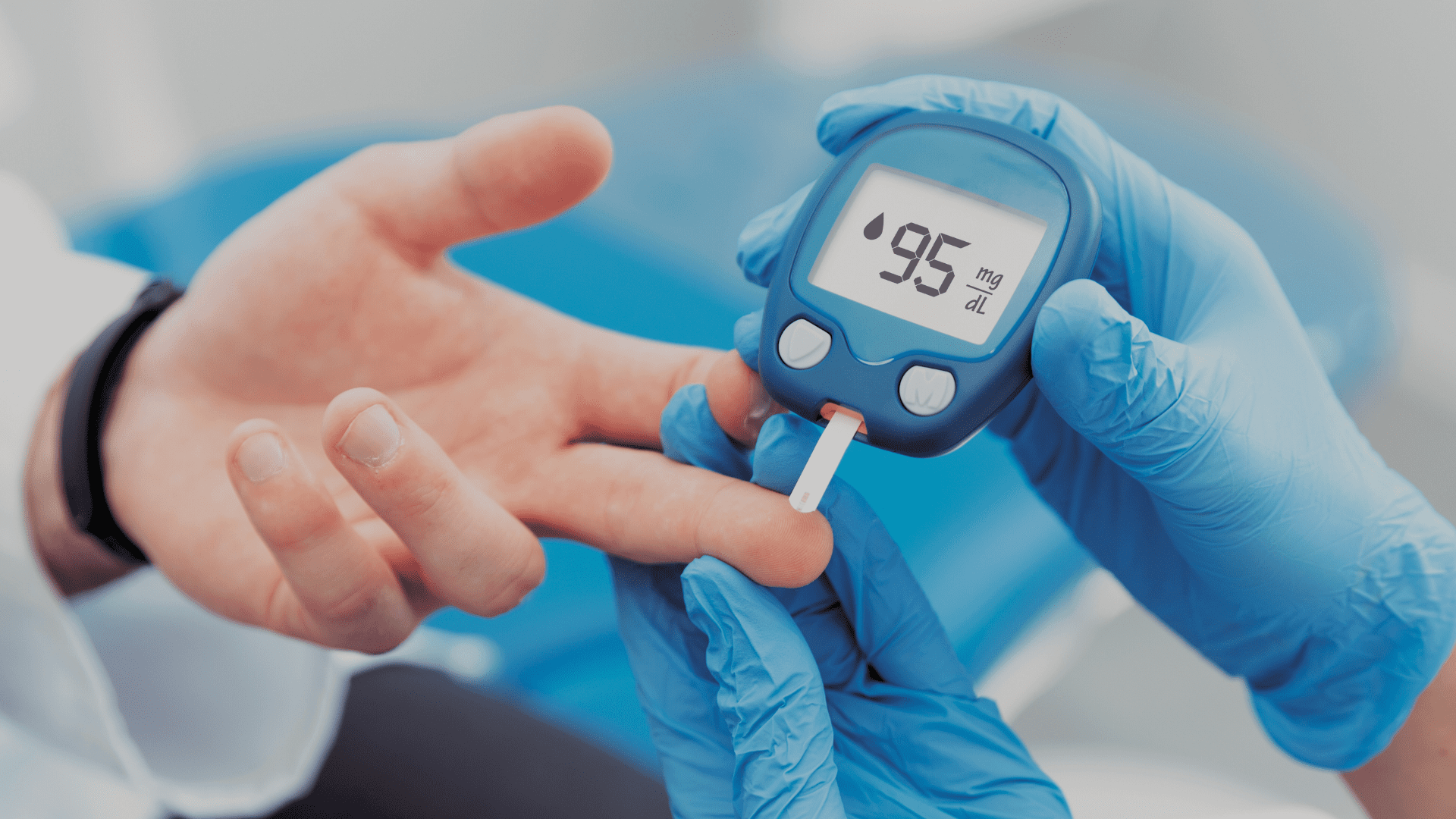

Scientists just found an all-new way to predict who might get type 2 diabetes, and it has a lot to do with what’s floating around in your blood. Researchers from Mass General Brigham and Albert Einstein College of Medicine spent 26 years tracking over 23,000 people. They wanted to see why some people get diabetes while others don’t. They examined “metabolites,” tiny molecules in the blood that appear after the body processes food or exercise. Here is what they found.

The study included 23,634 individuals from many different ethnic backgrounds. This matters because diabetes doesn’t affect every group the same way. For context, current data shows that:

- American Indians/Alaska Natives have the highest rates of diabetes at about 14.5%.

- Black/African Americans are at about 12.1%.

- Hispanic/Latino populations are around 11.8%.

- Asian Americans sit at 9.5%.

- White populations have the lowest rate at about 7.4%.

By studying such a diverse group, the researchers identified 235 molecules associated with diabetes risk. Of those, 67 were new discoveries.

Advertisement

The team picked out 44 specific molecules to create a “signature.” This signature is better at predicting if you’ll get sick than the standard tests doctors use now. But it’s not just about biology. The study found that obesity and what you eat, specifically red meat, sugary drinks, and coffee, directly change these molecules. If you eat a lot of red meat, certain markers in your blood go up, and those markers are the same ones linked to diabetes.

Dr. Jun Li, one of the lead authors, said that a person’s lifestyle habits have a huge impact on these specific molecules. So, your diet isn’t just “good” or “bad” in a general sense; it’s actually changing your blood chemistry in ways researchers can now track.

But here is the catch: this doesn’t mean we have a cure yet. The researchers said they still need more clinical trials to prove these molecules cause the disease, rather than just being a warning sign. The goal for the future is to use this data to create prevention plans that are specific to you, instead of giving everyone the same generic advice.